In Colorado Springs, the mayor is working hard to change an existing ordinance (which forbids anyone to lie down anywhere) so it will criminalize sitting down anywhere in the city. In San Francisco, the mayor doesn’t care whether people experiencing homelessness are sitting, lying, standing straight up, or kneeling in prayer. Whatever their posture, he vows to chase them all out of there before the Super Bowl. Currently, one-third of American cities have laws against sleeping outside. Last week, House the Homeless talked about the “statement of interest” filed by the Department of Justice regarding a current case brought by Idaho Legal Aid Services and the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty.

At the core of this topic is the question of whether anti-camping ordinances are constitutional or not. It is a “currently unsettled area of the law” about which various courts disagree. That is what Bell v. City of Boise is about, and the outcome will have massive policy implications throughout the system.

This started 9 years ago, with a Los Angeles ordinance under which people experiencing homelessness could be arrested for sleeping on the street even when no shelter beds were available. Since there were twice as many homeless people as shelter beds, this meant that, on any given night, half the homeless population of LA was vulnerable to arrest.

Jones v. City of Los Angeles

The ACLU and the National Lawyers Guild filed suit against the City of Los Angeles. Judge Kim M. Wardlaw of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ordered that the draconian ordinance should no longer be enforced, stating:

The Eighth Amendment prohibits the City from punishing involuntary sitting, lying, or sleeping on public sidewalks that is an unavoidable consequence of being human and homeless without shelter in the City of Los Angeles.

At the time, there was great rejoicing. Mark Rosenbaum, the ACLU attorney who had argued the case, called Judge Wardlaw’s decision “the most significant judicial opinion involving homelessness in the history of the nation.” Sadly, it didn’t turn out that way. But thanks to more recent developments such as Bell v. City of Boise, that bold prediction might still come true.

A year and a half after Judge Wardlaw’s ruling, Los Angeles and the ACLU finally quit arguing about what would happen next, and reached an agreement that no one was really happy with—in other words, a workable compromise. As long as they stayed 10 feet away from entrances and driveways, homeless people could sleep on city streets between the hours of 9 p.m. and 6 a.m. But the police could start enforcing the no-lying ordinance again as soon as the city built 1,250 units of supportive housing. Not shelter beds, but actual places where a person could settle in and get help to set her or his life on track.

And, says journalist Evan George, they went on to quibble about whether housing units that were already in the process of construction would count. The police department complained about “shelter-resistant” street people who refused to claim available beds. A law professor did a study and found “a median of just four shelter beds available on a given night when the LAPD was counting more than 1,000 people sleeping on the street.” Homeless advocates pointed out that, even if there had been enough shelter beds, it’s not the same thing as supportive permanent housing.

Several years later, when street people were allowed to return to a physically cleaned-up Skid Row, Councilman Bill Rosendahl was called upon by his constituents to explain the situation:

On October 15, 2007, the City entered into a legally binding settlement, agreeing not to enforce the law prohibiting sleeping on the streets, between the hours of 9 p.m. and 6 a.m. until it builds 1,250 units of permanent supportive housing. The City entered this agreement after the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals…found that the law against sleeping on the streets amounted to cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the 8th Amendment…,

In the words of Evan George, these were the consequences:

By agreeing to the settlement, the ACLU has given up any claim of using the Ninth Circuit court ruling as precedent for future lawsuits. However…attorneys for the homeless may still cite the decision in future lawsuits.

In other words, even though Judge Wardlaw’s ruling was vacated, the reasoning behind it was sound, and valid enough to use in Bell v. City of Boise, which is why the Justice Department recently wrote:

The statement of interest advocates for the application of the analysis set forth in Jones v. City of Los Angeles, a Ninth Circuit decision that was subsequently vacated pursuant to a settlement. In Jones, the court considered whether the city of Los Angeles provided sufficient shelter space to accommodate the homeless population. The court found that, on nights when individuals are unable to secure shelter space, enforcement of anti-camping ordinances violated their constitutional rights.

Reactions?

Source: “ACLU of Southern California Wins Historic Victory in Homeless Rights Case,” ACLU.org, 04/14/06

Source: “City, ACLU Settle Street Sleeping Case,” LADowntownNews.com, 10/15/07

Source: “Skid Row Homeless Say LAPD Is Trying to Bully Them off Their Freshly Cleaned Turf,” LAWeekly.com, 06/22/12

Source: “Justice Department Files Brief to Address the Criminalization of Homelessness.” Justice.gov, 08/06/15

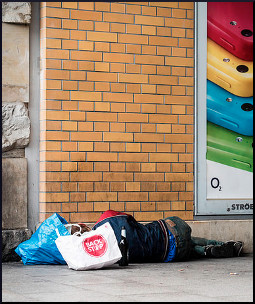

Image by Sascha Kohlmann