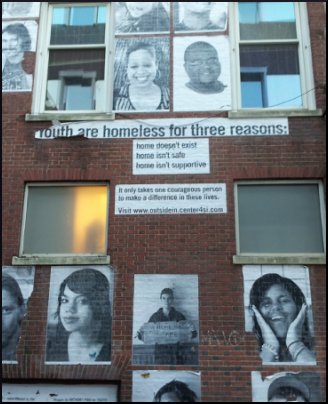

Last week, House the Homeless mentioned the time when agencies in Massachusetts received a “planning grant” of $120,000 to “identify the causes of transition-age homelessness.” We would have told them for free. The cause of transition-age homelessness is: A lot of kids, when they leave the foster care system, don’t have livable incomes and, as a result, don’t have any place to live. Bada-bing!

John Chafee was a U.S. Senator from Rhode Island who sponsored legislation to help ex-foster kids. What does the John Chafee Foster Care Independence Program do for youth on their journey to self-sufficiency?

The program is intended to serve youth who are likely to remain in foster care until age 18, youth who, after attaining 16 years of age, have left foster care for kinship guardianship or adoption, and young adults ages 18-21 who have ‘aged out’ of the foster care system.

The Chafee Act also allowed for Medicaid coverage to be extended to age 21, at the discretion of each individual state, for youths emancipated from foster care. If the particular state wants to, it can use up to one-third of its funding to pay for room and board for emancipated youths between 18 and 21. The federal government supplies most of the cost and the state kicks in some.

On paper, this program met various needs on the road to independent adulthood — education, employment, housing, financial management, and “assured connections to caring adults for older youth in foster care.” In reality, some states gave the federal money back, rather than bothering to carry out the Chafee Act requirements. (Incidentally, speaking of money, a later adjustment raised from $1,000 to $10,000 the amount of savings a young person is allowed to have, and still receive help. One wonders how many emancipated foster kids struggle with a too-much-savings problem!)

Accountability

The government agencies in charge needed to know whether their efforts were actually doing any good. They wanted to know the outcomes, including “educational attainment, employment, avoidance of dependency, homelessness, non-marital childbirth, high-risk behaviors, and incarceration.” For several years, little was done to advance toward this goal. Apparently, nobody started keeping track, except the occasional oddball grad student or nonprofit foundation, so we don’t know much about the young lives at stake here. Finally in 2008, the states were ordered to start doing followups by October of 2010.

Meanwhile, the Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative started to figure things out by paying attention to various studies of the quality of independent living programs and their results. Its April 2010 report made the excellent point that kids with families have a long grace period before they are expected to be full adults. If a young person is settled and independent by age 25, that’s considered good. Former foster kids, with a lot less going for them, are expected to pull themselves together and function as self-sufficient members of society at 18.

And some do, but this report does not find the success rate impressive:

In general, programs have been found to be ineffective in meeting the needs of young people in the areas of education and employment, economic well-being, housing, delinquency, pregnancy, and receipt of needed documentation.

Independent living programs were found to be “primarily checklists and involved classes for youth in foster care.” The paucity of implementation led the Government Accountability Office to take a peek. Its 2004 report wore a frowny face:

The GAO found gaps in the availability of mental health services, mentoring services, and securing safe and suitable housing, particularly in rural areas.

In response to the GAO survey, 49 states reported increased coordination with federal, state and local programs that could provide or supplement independent living services. In follow-up interviews with child welfare administrators, however, the GAO found that most were unaware of these services.

The accountability agency identified the lack of uniformity in the states’ information-gathering that made them unable to coordinate with each other and with the federal government to combine their numbers and make any sense out of things. Academia supplied some of the missing answers, which involved “extremely poor outcomes” and even “dismal outcomes” for large numbers of young people.

A University of Chicago study of kids in three states said:

In comparison with their peers, they are, on average, less likely to have a high school diploma, less likely to be pursuing higher education, less likely to be earning a living wage, more likely to have experienced economic hardships, more likely to have had a child outside of wedlock, and more likely to become involved with the criminal justice system.

Another study found that only about half of ex-foster kids had a high school diploma or equivalent. At age 21, only about a third had any college experience, and less than 2% of them ever finished college. And get this. If we ever needed proof that foster kids are emotionally deprived:

The Midwest Evaluation found that 71% of females aging out of foster care become pregnant before 21 compared to the 34% of the general population of females. Repeat pregnancies were common among females aging out of foster care… Half of the young men […] reported having gotten a female pregnant, compared to 19% in the comparison group…

Here’s a statistic that will knock your socks off: Former foster kids are 10 times as likely to have been arrested, since age 18, than young adults their age who were not foster kids. And, by the very nature of street life, and governmental neglect, and ingrained distrust of the establishment in any form, there is no way to even guess how many young people turned loose from the foster system are currently experiencing homelessness. Here comes an even more dizzying number:

… [A]llowing young people to age out of foster care to live on their own also has a significant fiscal impact on society in terms of educational outcomes, unplanned parenthood, and criminal justice system costs… Cutler Consulting has estimated that the cost of the outcome differences between young people aging out of foster care and the general population is nearly $5.7 billion for each annual cohort of young people leaving care.

Reactions?

Source: “Program Description,” HHS.gov, 06/28/12

Source: “Chafee Plus Ten: A Vision for the Next Decade,” Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative, April 2010

Image by Todd Van Hoosear.