There are three kinds of “first-person” accounts of homelessness, the first being, of course, narratives that originate with the authentic homeless. They tell their own stories and the stories of other street people their lives have intersected with, which is almost the same thing. It’s a kind of autobiography-by-proxy, and, a lot of times, it’s the first, last, and the only time these stories have been told, because we are speakers for the dead.

An example of this type of writer is Ace Backwords. Another, not surprisingly, is Richard R. Troxell. His Looking Up At the Bottom Line is not just an explanation of the Universal Living Wage, and not just a manual on how to change the world nonviolently and with style. Interspersed among the campaigns and triumphs are many stories of individual people who are experiencing homelessness.

The second category, which we see a lot of, is objective reportage from both professional and citizen journalists, and other allies who work on behalf of the homeless to tell their stories.

Then, there are journalists and allies who experience homelessness themselves, in a voluntary and temporary way. Why? As an exercise in empathy, a personal learning experience, or an instrument of spiritual growth. These quests usually originate from sincere intention, to raise awareness, to raise funds, or just to be writing about something significant rather than trivial. In any case, for such adventurers, the project is not complete until they report back to their housed peers, sharing anecdotes and insights.

Impersonation has always been a powerful tool in the writer’s arsenal. In the early 1960s, James Baldwin, Richard Wright, and many others had written firsthand accounts of the African-American experience. But attention really fastened on the subject after the publication of Black Like Me. The author was John Howard Griffin, a white man who had disguised himself and passed as a member of the group then called Negro. It may not be fair or reasonable, but when a Caucasian related his “first-person” account of being black, other Caucasians paid attention.

There are different opinions about simulated homelessness. To make a project out of visiting that world is kind of like boarding a pirate ship at a theme park. It might be very realistic, but it’s not real. People who seriously have no choice about homelessness can be forgiven for encouraging these “tourists” to go and find another hobby. But no matter how anybody feels about it, experimental homelessness does garner press attention, whether the participants are church youth groups or individuals with a literary purpose in mind.

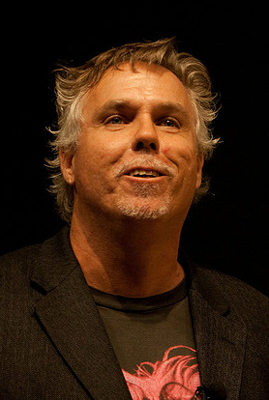

Mark Horvath has covered every possible category or genre of writing about homelessness, and shows no sign of stopping any time soon. Let us quote from Adam Polaski’s very thorough profile of Horvath:

He’s the founder of a website called InvisiblePeople.tv, where he publishes unedited videos of homeless people talking about their lives. He’s also the founder of a website called We Are Visible, a community and tutorial resource that empowers homeless people to set up their own free social media accounts to tell their own story.

As a public speaker, Horvath is both versatile and energizing. Polaski describes him as a cause-marketing expert, who started out wanting to be a professional musician, somehow wound up as a television executive instead, and then lost it all when addiction became the driving force of his life. Anybody could have seen that coming — just another Hollywood Boulevard junkie.

Sixteen years ago, Horvath attained sobriety. In a recent and fascinating article, the man himself describes the turnaround:

I am one of the lucky ones. I got out of street homelessness rather quickly. But it took eight years of living in a church program before I had a normal life and was no longer homeless.

He saved up, got an apartment and better jobs, and eventually left Los Angeles and climbed back up as far as the middle class, with a three-bedroom house in Missouri. But a few years ago, work dried up, as it has for so many of us. Horvath was living off credit cards when a job offer came, a really good one, so he went back to LA. Three months later, the company underwent massive downsizing and Horvath was once again unemployed, only now with even more bills than ever. The house back in Missouri didn’t sell, even though he was willing to take a tremendous loss just to be disencumbered of it.

Horvath speaks of the…

… wonderful people who helped me get through that dark time. Several helped pay my rent. New Hope, a church lead by Charles Lee, gave me food cards. And many of you took me out to eat. It is nothing short of a miracle that I didn’t end up back on the streets during that time.

And that was the crisis to which he responded by starting InvisiblePeople.tv. Polaski describes Horvath’s primary mission as “to make a name for the homeless and heighten awareness about the conditions of homeless people in the United States.” Polaski says,

So far, people perceive InvisiblePeople.tv and We Are Visible as positive online movements to raise awareness about complicated social issues. Horvath has become such a well-known advocate that his voice can make some serious waves… He’s driven around the country three times visiting homeless communities, filming footage and amassing insane amounts of knowledge about the housing crisis in the United States.

Now, here is the most recent plot twist. Mark Horvath will soon be technically homeless again, this time voluntarily. With another extensive (and generously supported) InvisiblePeople.tv road trip coming up, it doesn’t make sense to keep an apartment. The furniture is going to newly-housed families, and the homeless advocate is hitting the road until November, and leaving things open-ended after that. It’s a courageous way to proceed.

Reactions?

Source: “Mark Horvath: Shattering the ‘Self-Made Man’ Myth,” GoodMenProject, 05/06/11

Source: “Facing My Biggest Fear: Homeless In 30 Days!,” HardlyNormal.com, 05/29/11

Image by Randy Stewart, used under its Creative Commons license.