Last time, we outlined some of the issues surrounding the revitalization project planned for the Waller Creek corridor in downtown Austin, Texas. The first stage, the tunnel that will divert floodwaters, has begun. Businesses logically fear ruination by water damage, so once the threat of flooding is removed, this will encourage the growth of new businesses and, of course, increase the downtown property values and thus the tax base.

You’d think it would be possible to get even that far without objections, but you’d be mistaken. Even though the property owners in the immediate area, comprising Tax Increment Financing Reinvestment Zone No. 17, will be paying for a lot of the upfront costs, the city will be responsible for all the upkeep of the tunnel after 20 years (and, in this context, 20 years tends to slide by quickly). The city and county are paying now, but here’s an interesting footnote, courtesy of Wells Dunbar of The Austin Chronicle:

But the council also agreed to help fund the project via a small ‘drainage’ increase on Austin Water utility bills, an approximate 40-cent increase expected to ultimately collect more than $50 million.

That news prompted Brian Rodgers, co-founder of ChangeAustin.org, to ask the reporter a rhetorical question:

Why should all utility customers be required to subsidize Waller Creek landowners with $55 million from a regressive new drainage rate hike?

The opinion is shared by others, such as an online commentator called “Beano,” who writes,

This is about private gain from public investment. The property owners along this creek bought knowing they were in a flood zone. If they want something nicer and less flood prone, the rest of Austin should not be asked to pay for it.

Another citizen, known as “Big Texan,” adds,

It would be nice if the City Council would put limits on any commitments associated with this ‘project’. The idea of another unfunded and open-ended obligation is reckless.

But what’s done is done. The TIF zone is set up, ground has been broken for the tunnel, and the whole project is underway. Once the tunnel is finished, then the real work begins — the renovation of the above-ground area within the zone: Waller Creek and its surroundings.

The trouble is, from a certain perspective, this whole project looks like one big plot to rid Austin of its people experiencing homelessness — and not by housing them, but by shoving them out of the landscape. Ejecting the homeless is always a hoped-for side benefit when any city undertakes major public works or, for instance, prepares to host the Olympics or a political convention.

Civic leaders and politicians are usually too PR-savvy to come right out and say it, but locals who offer their opinions to the editorial pages and online comment threads can be quite unapologetically frank about the importance of street-people removal on their list of priorities.

Controversy has swirled around the massive and many-faceted Waller Creek master plan since it was conceived, making Austin an ideal case study for what happens when settled, monied interests clash with the needs of the ever-increasing number of the urban homeless. Many different populations will be affected in many different ways.

This is reflected by the composition of the Waller Creek Citizen Advisory Committee. And it is not the only one with an interest in the project. For instance, let’s take the homeless, and ask a question that, one hopes, has been asked by at least somebody on the Citizen Advisory Committee. With a big honkin’ civic project like this going on, what efforts are being made to hire the homeless?

As another Austin Chronicle reporter, Marc Savlov, pointed out, the majority of Austin’s homeless are people who are “struggling to regain a functioning, solid foothold into society-at-large.” Many of them are the working homeless, whom Richard R. Troxell calls the “economic homeless.” Yes, many homeless people do work, and more would work if they could get jobs, and many who are already working would welcome the chance to get better jobs. Savlov says,

For sleeping arrangements, a few pitch their tents as far south as Stassney Lane or West Gate Boulevard, coming into the Downtown area to work at steady employment ranging from roofing companies to construction to maintenance gigs. But none of their day jobs straight-pay enough of a living wage to secure and maintain what you and I would call a home: four walls, a roof, first and last months’ deposit, plus real-world essentials such as utilities and a phone.

Although some of the downtown businesses make some kind of effort to alleviate the symptoms of homelessness, not a lot is being done to solve the underlying problems. The journalist quoted Richard, and we can’t do better here than to quote him again:

Livable incomes breaks down into two factions, those who can work and those who can’t work. For those who can work, we’re promoting the Universal Living Wage, which goes to fix the federal minimum wage, $7.25 an hour, which is currently insufficient to get by on. Our goal is to take it from a federal minimum wage to a universal living wage. Even the U.S. Conference of Mayors, year after year, when asked what the single greatest contributor to homelessness is, says it’s the fact that you can work a full-time, minimum-wage job and not be able to afford basic food, clothing, shelter.

It seems like this should be fairly self-evident, but apparently it’s not quite clear to many solid citizens who have the good fortune to be employed and housed. If people have jobs, they buy stuff. They are magically transformed into customers.

Why can’t merchants and housed citizens learn to see homeless people as potential customers? After all, America did something that would not have been imaginable in the 1960s. We managed the mind-bending feat of learning how to see the Red Chinese as potential customers. (Unfortunately, the noble experiment of normalizing relations with China turned out somewhat differently than envisioned. We buy a bunch of crap from them.) But the point is, compared to that great leap of imagination, picturing homeless Americans as people who might actually go into stores and spend money ought to be easy.

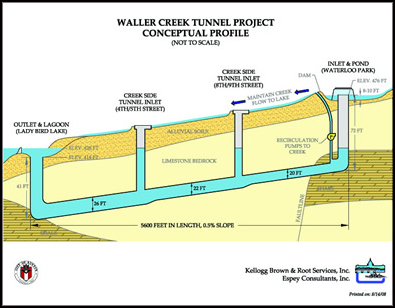

So, Austin, what are you doing about hiring the homeless for this ambitious, multi-staged, multi-million-dollar project? And then, there’s this. Check out the contractor’s name on the Conceptual Profile of the tunnel: Kellogg Brown & Root. Yes, KBR of Iraq war, military-contractor fame. Considering the outrageous pile of money the company has made from that adventure, how about a little reciprocation, on this tunnel project?

I challenge the contractors involved in the Waller Creek Project to use Veterans, Homeless Veterans and Formerly Homeless Veterans to make up 51% of the employed people involved in the construction of this project.

Richard R.Troxell

Viet Nam Veteran- Marines

Reactions?

Source: “Private conservancy outlines plan to rescue, revive Waller Creek,” The Statesman, 04/27/11

Source: “Money Flows to Waller Creek,” The Austin Chronicle, 02/25/11

Source: “DAA Proposes New Anti-Solicitation Ordinance,” The Austin Chronicle, 10/09/09

Image of Conceptual Tunnel Profile, used under Fair Use: Reporting.