It was just over a year ago when B. N. Duncan died at age 65, and he is still missed daily in his old haunts, the streets of Berkeley, California. Duncan’s death and the memorial held for him were covered by a number of publications. He even made the CBS Evening News, where, in a story titled “Documenting the Homeless with Dignity,” John Blackstone told the world how Duncan was remembered by the street people he has found endlessly fascinating.

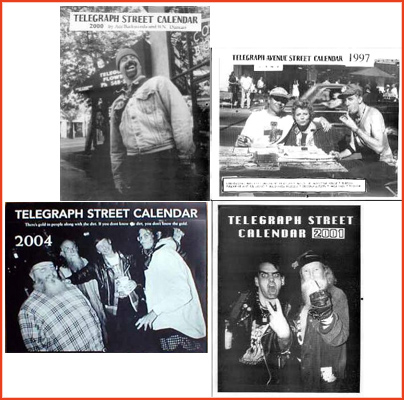

A fixture of the Berkeley scene, Duncan was always going around photographing the floating population, and many of his photos have ended up in the Telegraph Street Calendar, a unique cultural artifact that was produced for 15 years throughout the ’90s and in the early 2000s. His subjects thanked him for it. As one friend explained, street people don’t even look in mirrors, so it can be a touching and empowering experience for them to be represented and commemorated in this way. The story quotes Elaine Duncan, the photographer’s sister, who said,

He was a voice where there was no voice, and this meant a great deal to him.

Though Duncan could be something of a crusty character, his interest and compassion were endless, and he derived more enjoyment from getting to know the human flotsam of Berkeley than most solid citizens find in their own family circles. He took everybody with equal seriousness and equal light-heartedness. His publisher called him a genius.

In poor health toward the end of his life, Duncan himself was protected from the elements by his small apartment, but he spent his days among the ever-shifting yet never-changing denizens of this university town.

In Looking Up at the Bottom Line, Richard R. Troxell makes an excellent point:

We find that, while the majority of people experiencing homelessness may continue to reside in the same place, they are referred as ‘transients’… When you label someone as ‘transient,’ it paints a picture that he or she is just passing through. It implies that such persons have no relationship to our community and, therefore, we have no relationship to, and no responsibility for them.

Nowhere is this permanence of “transients” more evident than in Berkeley. There are people who have been on the scene for 10 or 20 years, or even since the 60s, when Berkeley was one of the centers of the world. They include people suffering from mental illness, drug dependency, alcoholism, and just general inability to handle modern life — folks who are so disconnected that even joining the “working poor” is far above anything they could aspire to. Even the dream of qualifying for any kind of subsidized housing is beyond what many of these lost souls could ever hope to achieve.

A lucky few get by on Social Security payments, while many depend on panhandling and various ingenious ways of scraping together a few bucks. But, despite their ongoing problems and the rigors of addiction recovery and the temptation to give up all hope, the homeless population of Berkeley contains the highest concentration of feisty community activists anywhere. They’re always out there demonstrating for something or protesting against something, and social justice is on their minds 24/7. The ongoing struggle for People’s Park was a recurring theme in the calendars, and the world-famous Naked Guy of Berkeley appeared in its pages more than once.

B. N. Duncan was not the only force behind the Telegraph Street Calendar, which became a tradition for the local people experiencing homelessness who have appeared in its pages. Duncan’s partner in creativity during those years was cartoonist/street chronicler Ace Backwords, who admits to letting the very first printing of the work hit the streets with a typo on its front cover — “calender” instead of “calendar.”

Back in 2002, Gina Comparini interviewed Backwords for the Berkeley Daily Planet about the yearly social document which included not only photos of the street people, but samples of their artwork, cartoons, and statements to the world. Depending on the circumstances, 700 to 2,000 copies of each edition of the calendar were published, with the profits distributed to the participants. Comparini quotes Backwords:

It’s gratifying that what started as a personal thing now means so much to so many people… [W]e try to show them as people first, without the stereotypes… We’re showing them as creative people trying to live productive lives.

Like Duncan, Backwords has always felt compelled to bring these stories to light. Sadly, many of the biographies of street people have ended up being memorial pieces that he had written after their suicides. But he has also certainly celebrated the living, putting many hundreds of hours of labor and many donated dollars into a CD compilation of the work of the various street musicians indigenous to the area.

In yet another tribute to Duncan, community activist Dan McMullan wrote,

The calendar he co-produced had the wonderful effect of showing people that we walk by and ignore every day, as something special and worthy of note… I was always amazed how many students bought his calendars to send back home to show the family and friends what a wild and original place they were calling home for the next four years or so.

Source: “Documenting the Homeless with Dignity,” CBSNews.com, 08/09/09

Source: “Telegraph calendar records street’s spirit and mood,” The Berkeley Daily Planet, 01/12/02

Source: “B.N. Duncan: A Telegraph Avenue Fixture,” The Berkeley Daily Planet, 07/30/09

Images of the Telegraph Street Calendars courtesy of Ace Backwords, used with permission.