RawStory.com just published a lengthy article titled “Older and sicker: How America’s homeless population has changed.”

The writer is Margot Kushel, Professor of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. California is always worth keeping an eye on, because what happens there tends to spread to the rest of the country. As always, House the Homeless recommends that interested parties read the entire work, but here some key points.

For starters, about 20% (or one in five) of all the people experiencing homelessness in America are in California, a state with an unprecedented water shortage and a proneness to wildfires – not a good combination, especially for people whose only kitchen may be a campfire. The El Niño weather event will have some benefits, but too much water in too short a time can never bring happy results. Mudslides cover the houses of celebrities and CEOs, and torrents drown people who sleep along riverbeds.

On any day of the year about half a million cold, overheated, or rain-soaked Americans have no place to call home. A lot of adrift people go to urban areas if they can, because that is where the services are. In California, housing costs are the highest of any state, and the major cities are frighteningly expensive even at the best of times. Oakland, always on the scruffier side, is where Dr. Kushel’s research team has tracked the lives of 350 homeless subjects since the summer of 2013. About people over 50, she says:

In the United States, more than 30 percent of renters and 23 percent of homeowners aged 50 and older spend more than half of their household income on rent. This makes it hard to pay for food and medicine, and puts them at high risk of becoming homeless.

And a lot of them do become homeless, just at the time of life when all the years of struggle are supposed to pay off. Many of the people in this study worked for decades at “low-skill, low-wage” jobs, barely able to keep up with present needs, but at least they had somewhere to live. Homelessness at any age is traumatic, but when a middle-aged person falls into it for the first time, the psychological trauma is considerable. In present-day America, half the people experiencing homelessness are over 50. What does this mean in practical terms? Kushel says:

When the homeless population was made up of a majority of younger adults, health care providers focused on treating substance use and mental health disorders, traumatic injuries and infections, many of which could be treated with short-term care. Now, with an older homeless population, health care providers have the difficult task of managing chronic diseases like diabetes and heart and lung disease. The point our study highlights is that the systems set up in the 1980s were not designed to serve an aging population.

About half of the older group are not new to homelessness, but have been in the wind for years, shuttling through the well-worn pathways that lead from shelter to jail to hospital to roadside camp to shelter to jail, on and on with endless variations but always the same old story. Their initiating traumas happened long ago, and their health situations have been deteriorating for years. Of the newer middle- and late-middle-aged homeless, Kushel says:

Their lives became derailed by job loss, illness, a new disability, the death of a loved one or an interaction with the criminal justice system.

Someone rooted in a stable lifestyle might be able to handle one of those tragedies, get through the difficulty, and make a recovery. But life-changing events tend to gang up on a person who is already in a vulnerable state. Troubles arrive in bunches, and the domino effect is alive and well. Once they hit the streets, the sick get sicker, and the previously healthy become sick.

A person who has a roof, electricity, and running water finds it difficult to deal with functional and/or cognitive impairments, multiple medications, special treatments like oxygen, strict dietary requirements, frequent medical appointments, and endless piles of hellish paperwork. For a homeless person, existing with an illness or disability is insanely difficult.

Homelessness shortens anyone’s life expectancy, and it’s not surprising that homeless old people “die at a rate four to five times what would be expected in the general population.” Dr. Kushel leaves us with a statement and two questions:

What policymakers and the general public need to recognize is that the homeless are aging faster than the general population in the U.S. This shift in the demographics has major implications for how municipalities and health care providers deal with homeless populations.

How do we adapt existing programs for homeless adults to meet the needs of an aging population?

And possibly even more intractable but fundamental: how do we stop older people from losing their homes?

Reactions?

Source: “Older and sicker: How America’s homeless population has changed

RawStory.com, 01/09/16

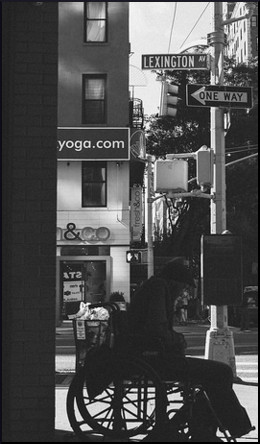

Image by Randy Sloan