In the United States over the past three decades, we have seen the invention of many new crimes (Driving While Hispanic, Voting While Black, Flying While Muslim, etc.) that are not officially on the books. But they are all too real for the people caught up in them. One of the new crimes is, apparently, Breathing While Homeless.

Check out this Executive Summary from the National Coalition for the Homeless (NCH). Its full title is “A Dream Denied: The Criminalization of Homelessness in U.S. Cities.” The numbers it utilized are a few years old, but if anyone imagines that things have improved since then, we have a nice bridge to sell them. (The bridge comes ready-equipped with a used tarpaulin, several sheets of prime cardboard, and… well, that’s all, actually.)

Depending on location, the statistics on people experiencing homelessness, and on available shelter space, may fluctuate. But the tendency to make homelessness a law enforcement problem continues to change for the worse. The authors of this report studied laws and practices in 224 cities and concluded,

This trend includes measures that target homeless persons by making it illegal to perform life-sustaining activities in public.

It mentions activities we have discussed on this blog, such as sitting, sleeping, camping, cooking, eating, or begging in public places. Of course, most cities figure out quickly that a two-pronged approach works best. Go after the people experiencing homelessness, AND go after the people who try to help, such as organizations that provide food. Here are some of the measures that have been taken by municipalities in the Orwellian name of “Quality of Life,” according to the NCH report:

* Legislation that makes it illegal to sleep, sit, or store personal belongings in public spaces in cities where people are forced to live in public spaces;

* Selective enforcement of more neutral laws, such as loitering or open container laws, against homeless persons;

* Sweeps of city areas where homeless persons are living to drive them out of the area, frequently resulting in the destruction of those persons’ personal property, including important personal documents and medication; and

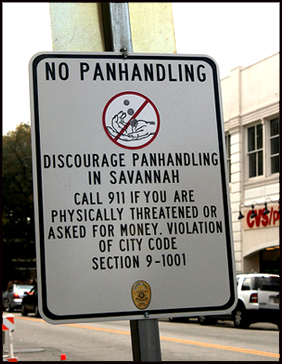

* Laws that punish people for begging or panhandling to move poor or homeless persons out of a city or downtown area.

There are of course numerous civil rights issues. Laws against vagrancy and loitering have always been constitutionally shaky, especially when the exact same behavior is accepted if the miscreant has a home where the police can tell them to go. (At Venice Beach, California, there used to be a street guy with a great line. If some tourist or local resident offended him, he would yell like a scolding parent, “Go to your room!”)

When a homeless person’s belongings are searched, or seized and arbitrarily destroyed, that’s Fourth Amendment territory. Begging for spare change just might be protected under the First Amendment. Then you’ve got the Eight Amendment, the one concerning cruel and unusual punishment, which applies when a person is accused of the heinous crime of sleeping.

So, what is accomplished by anti-homeless laws? They move people away from the centers, usually located in the inner city, where services such as food and job counseling are available. They make getting to these places even more difficult for people who must depend on buses (if they are lucky) or their own power of walking, to get around. Restrictive ordinances award thousands of homeless people with criminal records, as if they needed any more strikes against them in their efforts to emerge from the bottom layer of society. And the price of incarceration — don’t get us started. Jail is two or three times as expensive as supportive housing.

And then, there’s the little matter of international law. Our nation has signed on to global human rights agreements, prescribing humane treatment of people experiencing homelessness, which is fine for other countries but which we ourselves apparently don’t feel compelled to honor.

The report also offers some rays of light in a section called “Constructive Alternatives to Criminalization,” which is full of good ideas that have been either tried or contemplated by various localities. It offers helpful recommendations for the benefit of city governments, business groups, and the legal system, in dealing with these issues. Answers are proposed for both the chronic homeless, and the working poor or “economic homeless,” those who are unable to afford basic housing even though they have jobs.

However, House the Homeless has one big idea that would pretty much cover everything, and take away the need for each city to figure it out for themselves. It’s called the Universal Living Wage, and it will end homelessness for over 1,000,000 minimum-wage workers, and prevent economic homelessness for all 10.1 million minimum wage workers. You can also find out all about it in Richard R. Troxell’s book, Looking Up at the Bottom Line.

Reactions?

Source: “A Dream Denied: The Criminalization of Homelessness in U.S. Cities,” NationalHomeless.org

Image by quinn.anya (Quinn Dombrowski), used under its Creative Commons license.