It’s perfectly possible to be anti-war, or against a particular war, and still be pro-veteran. The government made a contract with these Americans. Yet a lot of returning veterans have not received and are not receiving what they are entitled to, because the government does not live up to its contractual obligation. It’s that simple.

In many cases, the federal government is not doing its job. In others, a state government falls short of fulfilling its purpose. On October 26, Jeremy Schwartz of the Austin American-Statesman blew the lid off a situation that affects more than 43,000 veterans in Bell County, Texas, which incidentally is the location of Fort Hood. A state law enacted in 1985 says that in any county where the population is over 200,000, there should be a full-time veterans service officer. Schwartz explains how the system is supposed to work:

While federal VA workers process claims, state, county and local veterans service officers play a crucial role in preparing what are increasingly complex disability claims for conditions such as traumatic brain injury. Officials say well-trained service officers can speed the process by submitting what they call “fully developed” claims, which include all the necessary medical and military records, making them easier to process.

Yet in Bell County, there is no full-time veterans service officer.

Of the 23 counties over 200,000, only Bell and Lubbock counties do not employ such officers, though Lubbock funds clerical staff to support a state officer, according to the Texas Veterans Commission.

The requirement is voluntary for smaller counties, but many have also hired at least part-time county veterans service officers, especially in recent years as service members have flooded home from Iraq and Afghanistan.

Since 1996, Schwartz writes, the task of liaising with veterans in Bell County has fallen on a volunteer, Jim Endicott. Although he is a former Veterans Administration general counsel, he only works part-time. Other volunteers and state employees help with the workload, but they can’t keep up, and volunteers are not required to take the annual training that the state requires for veterans services officers hired by counties. This is important, the writer points out, because the VA rules change constantly. If the workers are not familiar with the rules, how can they help vets successfully submit “fully developed” claims?

The troops on the ground

The veterans line up as early as 2 o’clock in the morning in hopes of being seen. (The question springs to mind, why not use an appointment system?) Frustrated by the inefficiency in their own locality, some journey to the designated offices in adjoining counties. Schwartz learned that in the past two years, more than a thousand local veterans who had signed in at the Temple office gave up and left before being seen. Bell County has issued 12,000 disabled-veteran license plates, a figure that hints at the extent of the problem.

Nevertheless, according to unnamed Bell County bureaucrats, complaints are few, even from veterans’ groups which presumably wield some influence. Jon Burrows, a Bell County judge, told the reporter that “there hasn’t been a need to hire a full-time county veterans service officer.” But he may be mistaken. The people on the job struggle under heavy caseloads. Schwartz says:

At one point last year, the VA’s Waco Regional Office, which serves veterans in Bell County and Central Texas, had the nation’s longest wait time for claims processing. Today, the average wait time to process a claim is 464 days in Waco — and 14,605 of the more than 26,000 pending cases have been sitting at least 125 days.

At last

Finally, in mid-November, the Bell County commissioners decided at their weekly meeting to add to their website a section containing information for veterans, to open up a phone line for questions from veterans, and to find office space for the veterans service officer who will be hired before the new year.

Issues still exist: a shortage of trained personnel, and of training for existing personnel, as well as the perceived need for a “one-stop shop” to make life a bit easier for disabled veterans and for people with other socioeconomic problems, such as being denied food stamps. Judge Burrows still maintains that the commissioners never even knew there were any unmet needs.

Jim Endicott, the volunteer liaison officer mentioned above, made the astonishing statement that he only sees “five or six veterans a year,” reports Alex Wukman of FME News Service. Mostly, Endicott just provides “referral and outreach” — in other words, connecting veterans with personnel at the Texas Veterans Commission.

****

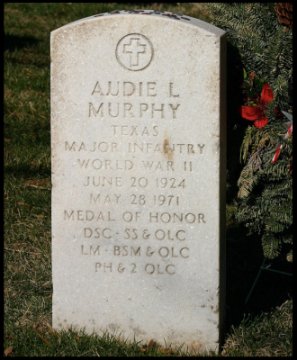

Note: War Hero Audie Murphy, though a Texan, was neither born nor buried in Bell County. Still, his story is very much worth knowing.

Reactions?

Source: “Despite state law, Bell County doesn’t employ veteran service officer“, Mystatesman.com, 10/26/13

Source: “Bell County to hire veterans service officer,” KDHNews.com, 11/13/13

Image by dbking