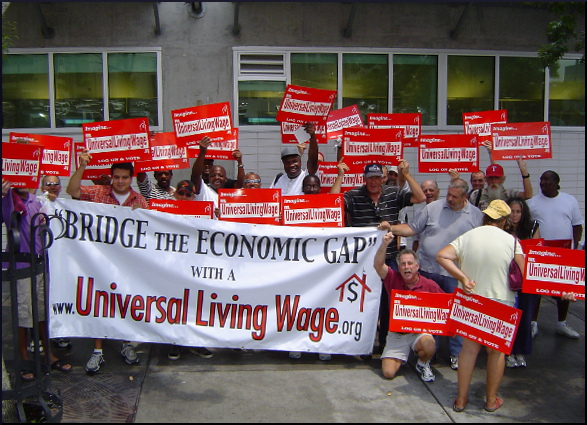

First, before getting into today’s topic, remember that next Tuesday is Bridge the Economic Gap Day, a day for action. Everything there is to say about this yearly tradition is contained in last year’s post, except that this time, it’s Tuesday, September 5, a week from today.

What is commensurate wage?

Since 2009, the federal hourly minimum wage has been $7.25, and the government has designated which workers it applies to. A whole separate area of law describes who can be paid less, and under what circumstances. There are two major exceptions to the requirement to pay minimum wage, and a person may fall under one or the other, or maybe even both.

It seems that the two can be mixed-and-matched, depending on the needs of the company that applies to be certified for the privilege of paying less. This is known as a commensurate wage, which has more dignity than “sub-minimum,” a word that could be termed meaningless, since “minimum” already means “least.”

One affected group are workers under 20 years old, who can be subject to a 90-day training period at $4.25 per hour. This is based on the idea that it will take them a while to get up to speed. During the probationary period, they will not only learn how to do the particular job, but will adapt to the mores of the workplace, such as timely arrival. When the probationary period ends, they will graduate to the ranks of regular employees. But more about this next week.

The federal rules

At the moment, the subject is disability. The Fair Labor Standards Act is enforced by the Wage-Hour Division (WHD) of the U.S. Department of Labor. For detail-oriented readers who want to follow up, the Field Operations Handbook is available online.

This excerpt is from section 64c00:

A subminimum wage is a wage paid a worker with a disability that is commensurate with that worker’s individual productivity as compared to the wage and productivity of experienced workers who do not have disabilities performing essentially the same type, quality, and quantity of work in the vicinity where the worker with a disability is employed.

Some examples of disabilities that may affect a worker’s earning or productive capacity include blindness, intellectual or developmental disability, mental retardation, cerebral palsy, alcoholism, drug addiction, and age.

Age alone is not considered a disability, but it is often concurrent with other disabling conditions. Disabilities range from mild to severe, in one or more of the following areas: “impairments in perception, conceptualization, language, memory, and control of attention, impulse, or motor function.”

The main thing to know is, an employer can pay a sub-minimum wage only when the disability impairs the person for the specific job. In other words, there would be no justification to pay a blind coffee-taster less.

For the employer, several rules apply. There are standards about work measurement and time studies and how the hourly commensurate rate should be calculated, and the company has to promise to reevaluate the job performance every six months or when the actual requirements of the job change.

The WHD civil servants are specially admonished about the importance of their oversight duties “because many of the workers with disabilities paid at sub-minimum wages have little knowledge of their rights under the various acts enforced by the WHD or may be unable to exercise them.”

Potential for mischief

Apparently, the three-months training period exception can be applied to disabled workers as well as those under 20. Some critics feel that, as a Washington state news editorial phrased it, 680 hours might be excessive:

That seems like a long time for a person to get the knack of a minimum-wage job, which by its very nature requires a relatively low level of skill. Would it really take a person 85 days (of eight-hour shifts) to learn a minimum-wage job?

In Seattle, these matters were hotly discussed when state and city minimum wages were adjusted. Washington’s Department of Labor & Industries had designated four sub-minimum wage categories, called “student learners,” “handicapped workers,” “adult learners,” and “student workers.”

Journalist Anna Minard wrote in her 2014 article:

The state has issued only five certificates in the last five years — four for individual handicapped adults, and one for student workers at a boarding school. But while the state program has been small, there’s no telling how many employers would apply for certificates with Seattle’s new higher wages — and how creatively they might try to interpret the existing but rarely used state codes. Opponents of training wages fear this could become a huge loophole for businesses to exploit.

One problem with the training period is that it encourages the unscrupulous employer to engage in an outright scam. Rather than retaining people at full pay, they might let them go when the probationary period is over, and hire a new batch of “trainees” at a discount. Michelle Chen wrote:

Advocates are also campaigning to stop federal subsidies for segregated sheltered workshops and “training” programs, where workers tend to languish indefinitely in jobs with virtually no redeeming educational value.

Please sign this petition!

House the Homeless hopes the reader, now armed with some background information, will take another step. The National Federation of the Blind is petitioning on behalf of all American workers with disabilities to end the Special Wage Certificates that allow the lower pay scale. The petition itself is a model of persuasive eloquence, and the points are worthy of consideration.

Reactions?

Source: “Field Operations Handbook,” DOL.gov, 09/21/16

Source: “Address flaws in bill creating ‘training wage’,” BellinghamHerald.com, 02/04/13

Source: “What’s the Deal with ‘Training Wages’?,” TheStranger.com, 05/28/14

Source: “People With Disabilities Aren’t Entitled to the Minimum Wage,” TheNation.com, 09/07/16

Image courtesy House the Homeless