A Book Review With Reflections on Society Over 50 Years After MLK

Why We Can’t Wait

Wages As a Civil Rights Issue

Imagine my delight routing through the 25¢ bins in west Texas when I came across a gem by the late, great Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Why We Can’t Wait, written in 1963. The subject of his book is the “Negro Revolution” in America. This is a fascinating, close and personal look at the American Civil Rights Movement at its most volatile moment. The good Reverend Doctor King tells the tale of a people, who after 200 years of enslavement and total economic thievery find the ultimate weapon to achieve a bloodless revolution: non-violence.

Dr. King crystallizes our understanding of the motivation behind the Civil Rights Movement/Revolution when he points out that even 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, the “American Negro” was living on a “lonely island of economic insecurity” while “in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.” Dr. King asserted that “Negroes” existed within two overlapping circles of segregation: one of color and one of poverty.

He went on to point out that even as late as 1963, there were two and one-half times as many unemployed Negros as whites. Dr. King contended that evidence of racial prejudice and economic repression continuing was clear by the fact that in 1963, the black median income was only half that of whites. Dr. King pointed out that, “Many white Americans, of good will, have never connected bigotry with economic exploitation.” He points out that while some sympathetic “whites” deplored prejudice, they “either tolerated or ignored economic injustice.”

It was generally acknowledged that the lowest-paid and the least stable jobs were earmarked for the “Negro.” Some might say the same is true of today’s “African Americans.” Others would say the impoverished base has simply broadened out and engulfed the weakest.

Reverend King speaks of the Jim Crow Laws that were enacted following the Emancipation Proclamation. These laws created living conditions that were “separate but equal.” These included segregated hospitals and cemeteries.

This is startlingly similar to the separate “Community Courts” now targeting people experiencing homelessness across America. Also falling into this category are today’s laws exclusively focused on people experiencing homelessness that include no camping, no soliciting, no sitting, no lying, no loitering, and laws regulating and limiting the feeding of people experiencing homelessness.

All of this comes at a time when the federal government sets a national federal minimum wage that affects tens of millions of our poorest citizens, both black and white. Remarkably, the last several U.S. Conference of Mayors Reports point out that this standard is so low that even while working 40 hours in a week, at this wage rate, no one can get into and keep basic rental housing anywhere in this country.

The movement to resist segregation drew its strength from the pulpit of the black churches. There was certainly strength in numbers, but at the same time, there was resistance from other African Americans. For example, when Dr. King was arrested and thrown into jail in Birmingham for marching in the streets, he received great resistance from the community and church leaders.

While in the Birmingham jail, he wrote a very long and impassioned open letter to these well-intended but sheepish leaders who felt his actions were rash, brash, and ahead of their time. The theme of the letter and the title of the book I write about here stems from Dr. King’s arguments as to “why we can’t wait.”

For starters, the people for whom Dr. King advocated have suffered physical attacks from snarling, vicious police dogs, stinging welts from indiscriminate police nightsticks, the raging force of fire hoses that were known to strip the bark off of trees, and sometimes the short end of a rope wielded by an angry mob.

Dr. King contends that there are two types of laws. He sees them as either just or unjust. He says it is our “moral responsibility” to disobey all unjust laws. The Reverend decries any unjust law and declares that it is “out of harmony with the moral law.”

He goes on to define any law that degrades human personality as unjust. He puts all segregation statutes into this category because segregation “distorts the world and damages the personality.” I would include in this Jim Crow laws and similarly all modern day Quality of Life ordinances that are applied against one faction of the citizenry and not others.

It is one thing to have a law that prevents sitting down and blocking a sidewalk, but it is entirely another when the targets of the laws or ordinances are mentally or physically disabled and have a legitimate need to sit or lie down while leaving room for reasonable passage. So as Dr. King aptly puts it, “Sometimes a law is ‘just’ on its face and unjust in its application.”

Dr. King states that defying a law in the face of imprisonment “is in reality expressing the highest respect for the law.” He points to the acts of Adolf Hitler and that technically they were “legal” while at the same time, “everything the Hungarian freedom fighters did in Hungary was illegal.” The world is upside down.

Regarding economics, Dr. King shines a very bright light on the fact that for more than two centuries, our forebears labored in this country without any wages whatsoever.

The Civil Rights actions of 1963 were non-violent acts of resistance, i.e., marching without a permit and direct non-violent defiance of segregation laws that declared “Whites only” and acts that involved civil disobedience at lunch counters. These came in department stores throughout the south and ultimately up and down the eastern seaboard. This came in department stores that gladly took the money from black patrons for items purchased but denied the Negro the right to sit at the lunch counters where White patrons also occupied seats.

As the action of non-violently occupying lunch counters continued, more and more Negroes volunteered to “learn” how to become non-violent as Gandhi had taught it. Wave after wave of Negroes, adults and children, practiced civil disobedience and resisted unjust segregationist laws and got themselves arrested while remaining non-violent.

They remained non-violent as their heads were crushed, the fire hoses and the dogs attacked them, and while they were choked with tear gas. Upon reflection, Dr. King stated that, “One of the wisest moves we made was introducing children into the Birmingham campaign.” They added energy, civility, and a voice for righteous indignation.

As the protests proceeded, Dr. King and the other leaders were very anxious to establish a dialogue with city leaders, businessmen, and others.

They sought:

- Desegregation of lunch counters, rest rooms, fitting rooms, and drinking fountains in variety and department stores.

- The upgrading and hiring of ‘Negroes’ on a non-discriminatory basis throughout the business and industrial community of Birmingham.

- The dropping of all charges against jailed demonstrators.

- The creation of a biracial committee to work out a timetable for desegregation in other areas of Birmingham life.

The resistance to these concessions was great. Many businessmen would rather face bankruptcy than concede to integration under pressure.

The 1963 Battle of Birmingham could be seen all the way to Washington, D.C. Attorney General Robert Kennedy sent an emissary, Burke Marshall, his chief civil-rights assistant, to open lines of communications. At the same time, the Commissioner of Public Safety, “Bull” Connor, literally turned up the water pressure of the fire hoses and all but ripped the flesh off of peaceful demonstrators.

The escalation was swift and instantly became violent. “Bull” Conner called in state troopers for backup. The Senior Citizens Committee, the white residents of Birmingham trying to find a solution to this human upheaval, met repeatedly. Then, one afternoon, 125 of these businessmen returning from lunch were stopped in their tracks when they witnessed that several thousand Negroes had marched into town.

The jails and recreation centers were so full of ongoing arrests that they could only arrest a handful more. They were face to face with thousands of black faces that were relentlessly singing freedom songs. One of the more resistant businessmen was quoted as saying, “You know, I’ve been thinking this through. We ought to be able to work something out.”

That same day, President John F. Kennedy used the opening sections of his press conference to call for compromise and acknowledged that both sides were now talking. By the end of the next day, every request/demand had been agreed upon. A peace pact had been signed. While this did not quell the angst, or even the bombings and the assassinations, there was at least a framework for congressional legislation that would ultimately come during the Johnson Administration.

In the meantime, Dr. King, in reflection, wrote that, “A social movement that only moves people is merely a revolt. A movement that changes both people and institutions is a revolution.” He was determined to integrate the schools and the factories.

It is said that power gives up nothing without a struggle, and so it is with the enslaving of people where their labor is stolen openly, or when a “Negro’s” freedom was periodically sold to that same slave, or when wages can still be correctly characterized as slave wages as they are today even though they are set by the federal government itself. This is the case today with the federal minimum wage being set at so low a level that it leaves a full-time worker firmly impoverished and unable to afford life’s basic necessities.

The emancipation of the American “Negro” led to the theoretical end of 200 years of a free pool of labor, that coupled with seemingly endless natural resources, catapulted this nation forward like no other in the history of mankind. American enterprise was firmly built upon this human resource. Today, American business remains unwilling to relinquish what still amounts to a vast human reservoir of cheap labor paid at poverty wages that continues to economically enslave workers.

Dr. King, recognizing that slavery was, in part, the engine of our Southern economy, reflected that slavery was beginning to loosen its grip and that there needed to be additional steps to end the “institution” of slavery. He felt that there should be some kind of reparations for the theft of the labor of these workers over the last 200 years.

In what some argued then and some still argue today is a kind of reverse discrimination, Dr. King recounted a conversation between himself and Prime Minster Nehru about how India addressed compensation for the past discriminations against the “untouchables” that is now reflected in India’s Constitution. It was established that if two applicants were to compete for acceptance to a college or university and one is from a high caste and one an “untouchable,” the “untouchable” would be hired.

This country adopted a version of that which came to be known as “affirmative action.” But if the cheated worker was to be compensated at a set fair wage, then the current federal minimum wage would have to be recast to resemble a Universal Living Wage. In this fashion, a full-time minimum-wage worker would be assured of working 40 hours in a week and being able to afford the basics as stated: food, clothing, and shelter (including utilities) — wherever that work is done throughout the United States.

Dr. King wrote about the irony of the lunch-counter sit-ins in Greensboro, N.C., and a night club comedian’s observation that, “had the demonstrators been served […] they could not have paid for the meal.”

Dr. King asks: What advantage is it to achieve integration if one simply becomes subject to financial servitude? Dr. King points out that, “The struggle for rights is, at the bottom, a struggle for opportunities.” The good Reverend wrote that “no amount of gold could provide just compensation for 200 years of exploitation and humiliation.” But, he asserted, “he can be compensated for his 200 years of robbed wages.”

Dr. King, while continuing to reflect on economic compensation, wrote that “while Negroes form the vast majority of America’s disadvantaged, there are millions of poor ‘Whites’ who would also benefit from A Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged.” Dr. King contended that:

The moral justification for special measures for ‘Negroes’ is rooted in the robberies inherent in the institution of slavery. Many poor ‘Whites’; however, were the derivative victims of slavery. As long as labor was cheapened by the involuntary servitude of the ‘Black man’, the freedom of ‘white labor’, especially in the South, was little more than a myth. It was free only to bargain from the depressed base imposed by slavery upon the whole labor market. Nor did this derivative bondage end when formal slavery gave way to the de-facto slavery of Economic Discrimination. To this day, the ‘White poor’ also suffer deprivation and the humiliation of poverty if not of color. They are chained by the weight of discrimination, though its badge of degradation does not mark them. It corrupts their lives, frustrates their opportunities and withers their education. In one sense, it is more evil for them because it has confused so many by prejudice that they have supported their own oppressors.

Dr. King harks back to the 1930s and the struggle by workers to organize to secure a living wage. He found it interesting to note that it was some of the same states that opposed the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s that opposed organizing for living wages in the 1930s.

The same can be said today. People who want to make their way forward off the back of others are strident in their march of oppression. They marginalize the vulnerable using the color of their skin, or the weight of their wallet, the level of their education, or their belief in their God.

Dr. King felt that a mutual support between organized labor and the civil rights movement was “not a matter of choice but a necessity.” I agree, but the AFL-CIO of today must shed itself of non-progressive thinking of yesteryear if it is to help the folks at the bottom today. The shopworn approach of “one size fits all” for our national minimum wage is folly at best and grossly repressive at worst.

We are a nation of a thousand-plus economies. It is important to recognize that a single federal minimum wage of, say, $10.00 an hour won’t get a single homeless, minimum-wage worker off the streets of our nation’s capitol. At the same time, $10.00 per hour would devastate small business in rural America.

A single federal minimum wage that only goes part of the way to the economic goal of escaping poverty only ensures economic slavery for every minimum-wage worker. And it makes no sense to set a wage that will crush small businesses all across rural America. It is no small wonder as to why small businesses continue to resist gulping changes that so affect these small engines of our economy.

If the AFL-CIO, that remained neutral during the civil rights movement, is to redeem itself as a level-headed, thinking advocacy organization, it will need to abandon this one-size-fits-all approach. Evidence of the failure of “one size fits all” rests in the fact that 3.5 million minimum-wage American workers under that policy will experience homelessness in this year, 2013.

If the union leaders of America are to be considered enlightened, they will need to acknowledge that we are a nation of a 1,000-plus economies, with the single most costly item in every American’s monthly budget being housing. And therefore, what we need to do to free the American minimum-wage worker, is to index the federal minimum wage to the local of housing.

In this fashion, anyone working 40 hours in a week, (be it at one job or more) — the individual “Black” or “White” — they will be able to afford basic food, clothing, and shelter (including utilities) wherever that work is done throughout the United States. This will conservatively end homelessness for over 1,000,000 minimum-wage workers and prevent Economic Homelessness for all 10.1 million minimum-wage workers.

These impoverished workers will then be in a position to avail themselves of America’s opportunities and chase the American Dream along with everyone else. Until then, they just be poor folks… white or black; it’s about green… some say it always has been.

Dr. King saw the 1950-1960s Civil Rights Movement and the events of 1963 in particular as a true beginning for the American “Negro,” the downtrodden, the oppressed, and the poor “Whites” everywhere. He saw unity among these groups as our strength and non-violence as our greatest weapon.

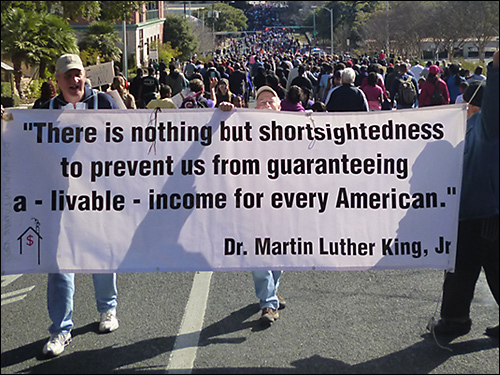

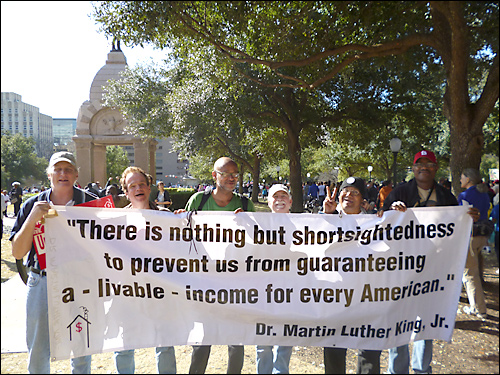

Final Note: House the Homeless borrowed a quote from the late, great Dr. King and it now adorns the Homeless Memorial in Austin, TX. “There is nothing but short sightedness to prevent a livable income for every American family.”

Join us in the fight for a Universal Living Wage!

Image by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Los Angeles District

Image by Elvin Wong

Image by uusc4all