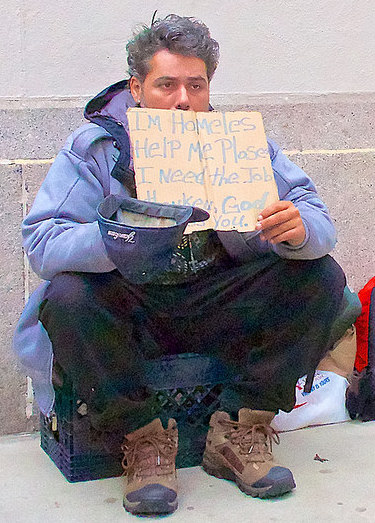

Last week we pointed out some of the mistaken ideas that housed people hold regarding people experiencing homelessness. Another of those widespread misconceptions is that “the homeless don’t want to work.” Let’s take as examples the same four subgroups we focused on in the discussion of mental illness, in the context of these particular demographics having very little mental illness or addiction issues.

First, mothers of children, who are homeless with their kids because of abandonment, domestic violence, or just plain not being able to afford housing. It’s easy to say, “Make them get jobs.” But what are their children supposed to do? Sure, school-age kids are supposed to be going to school. But that takes up very little time, compared to a work week. School days are typically much shorter than work shifts.

Who watches over and protects the child on the way to and from school? The kids have to get back and forth somehow, and their mother probably does not own a car, and, anyway, school escort duty might conflict with her work schedule. What if there is more than one child, and they go to different schools? What if the child is too young for school? Even if a working homeless mother could find day care, it probably costs more per hour than her own hourly wage.

More obstacles for homeless mothers

Often, night shift jobs are easier to snag, for obvious reasons. But even if she wants to, can a homeless mother work nights? Shelters have curfew rules. People have to be in by a certain time, they can’t just come and go as they please, or even as they need.

And how does the prospect of leaving the kids all night in a shelter full of strangers sound? Is there any homeless living situation that even allows children to be left overnight without parental supervision? Can their mother tuck them in to sleep in a van while she works? That sounds like a swell opportunity for child protective services to intervene and take away her parental rights.

Even in a best-case scenario, with a steady job, a homeless mother is likely to find work only on the lowest rungs of the economic ladder, in the type of job where after eight hours, she just might hear the manager say, “So-and-so didn’t show up, I need you to stay on for another shift.” What is she supposed to do, refuse and be fired? Quit? And be unemployed, and have a black mark on her record for being the kind of feckless creature who gets fired or quits?

And what about school holidays, and summertime, and kids being sick, and kids getting in trouble at school (sorry, it happens) with no parent available to come pick them up? And as far as those children themselves seeking employment, we still have child labor laws. Mothers and young kids are two very hard-pressed groups, who are unlikely to “Just get a job!”

Unaccompanied youth

We also talked about unaccompanied youth with nowhere to live except a relative’s couch or a friend’s unheated garage without running water or toilet. With any luck at all, a young person in this situation somehow manages to stay in middle school or high school, which in itself is a stunning accomplishment, and one that many are unable to sustain.

Not surprisingly, a lot of those kids drop out of school at or before the legal age. How employable are they? The answer to that question is so obvious we will not even insult the reader’s intelligence by bringing it up. Oh, and by the way, they are still teenagers, a category of people not famous for their stability or judgment, even when they are securely housed and regularly fed.

A special subgroup

In 2017, the United States of America, the richest country in the world, contained at least 32,000 homeless college students. Those are only the ones who allowed themselves to be counted, and many go to considerable trouble to prevent their situation from being generally known.

Even college students who are financially secure, with the full backing of their families and other advantages, have to put in a lot of hours of hard work for their grades. Sure, plenty of undergraduates also work, but with such split priorities they can’t get the full value from their education, so let’s not hold them up as models.

For a homeless youth, doing well in school means everything, because there is a genuine and exigent need to recoup the investment. All that struggle can’t end up being for naught. Getting enough education to secure employment and not be a public charge is this person’s job at this point in time. To expect him or her to also make enough money to set up a household is quite unreasonable.

Apparently, a lot of citizens don’t know that homeless college students even exist, so here is a short reading list that an advocate can offer to an unbeliever:

- “Behind the Problem of Student Homelessness“

- “This Is What It’s Like to Be Homeless in College“

- “1 In 10 College Students In Mass. Are Homeless. More Are Hungry. It’s Past Time We Recognize Their Reality“

- “The hidden problem of homelessness on college campuses“

- “Hunger And Homelessness Are Widespread Among College Students, Study Finds“

We also recommend…

Remember the survey of people experiencing homelessness in Austin, and how it showed that 47% of the respondents were too disabled to work? House the Homeless co-founder Richard R. Troxell reminds us, “This leaves about 52% who are capable of working. Another statistic that we unearthed is that these folks want to work… for Living Wages.”

Three Things to Know About Hunger and Homelessness Awareness Week

We are in the midst of Hunger and Homelessness Awareness Week, and it’s not too late to find a local activity that will welcome your participation. Whether your area of expertise is education, service, fundraising, or advocacy, you can make a difference.

The National Coalition for the Homeless and the National Student Campaign Against Hunger and Homelessness offer a useful resource, a downloadable PDF file called “Resolve to Fight Poverty.”

Now, this is the most important thing to know. Austin’s Annual Homeless Memorial Service

takes place on November 18, 2018 at sunrise (6:57 a.m.). The location is by the river at Auditorium Shores, South First and Riverside Drive (on the south side of Lady Bird Lake). As always, the event is created by House the Homeless.

Reactions?

Photo credit: Ed Yourdon on Visualhunt/CC BY-NC-SA