Last time we talked about some of the incidents described in Richard R. Troxell’s book, Looking Up at the Bottom Line. Back in 1989, there was talk of decommissioning Bergstrom Air Force Base, right outside Austin. Richard set out to gather support for the idea of turning the facility into a center for substance abuse treatment and job training.

It made sense, because a lot of the people experiencing homelessness who needed these services also happened to be veterans. But it was not to be. Richard wrote,

The city, in its wisdom, hired a consultant who said due to noise consideration that the airport would not be the most conducive place to conduct rehabilitation and job training for the homeless community. Apparently, it was good enough for thousands of veterans and all the mothers who gave birth at the base hospital, but it isn’t good enough for the homeless population?

The homeless are somehow perceived to be better off living on the street, in our parks, eating out of garbage cans, and now subject to arrest for sleeping in public!

This mindset is all too prevalent among people without a scrap of human empathy, who speak with a forked tongue. They give lip service to the idea of helping, but when a reasonable proposal appears on the horizon, all of a sudden it’s, “Oh, no, we can’t put our homeless veterans into a repurposed building.” More than likely, there isn’t as much profit in it for builders, either.

The same kind of thinking wants to tear down every makeshift lean-to and take away every packing crate because they are hazardous places to sleep, and not fit for human habitation. Some folks actually go so far as to piously assert that it is less dangerous for people to have no habitation at all. So the chorus is, “No, the homeless vets are much better off as they are, while we apply for federal funds and hire some contractors to make them a nice new building at some point in the future.”

The “s” word

It has become a trope or an urban legend that, on an average day, 22 American military veterans end their own lives. Not long ago, the Department of Veterans Affairs publicized the fact that the statistics from its first National Suicide Data Report have been misreported and misinterpreted, and the number is actually 20.6 per day. On learning that things have not been quite as bad as we thought, what else can we do but rejoice?

The first Suicide Report, issued in 2012, covered the years from 2005 to 2015, was misconstrued because people did not realize that the numbers included suicides not only of veterans but of active-duty servicemembers including National Guard and Reserve units. As Meaghan Mobbs phrased it in Psychology Today,

The failure to contextualize that figure, or any figure, results in a narrow focus on the number itself with a blind eye toward both its complexity and limitations.

Also, there has apparently been some misunderstanding about what exactly constitutes a veteran. “A common source of confusion” are the words used, although it would seem that the military would have had plenty of time, over the decades, to nail down that definition.

This brings up another point. Suicide is still attended by a great amount of stigma. For religious reasons, or for family loyalty reasons, people want to avoid filling in “suicide” on official forms, and it is still possible to fudge the paperwork. Although sometimes the cause is quite obvious, there must be many ambiguous deaths. Did someone drive off the road and over a cliff because they were surprised by a wild animal, or…? Also, these numbers do not include the thousands who commit slow suicide over time.

There is another layer of baffling complexity. Not only have the totals been misinterpreted, they may have been inaccurately reported. The record-keeping has certainly been incomplete. These stats are based on data from less than half of the states, and some of the non-reporting ones included gigantic veteran populations.

In an effort to grasp the essential numbers, the Veterans Administration consults state-generated death certificates, where a box can be checked if the deceased person ever served in the military. For states that do not submit their information, the numbers are extrapolated.

One valid question is, why does it take so long to pull all this data together and analyze it? We have computers now.

Last fall the updated VA National Suicide Data Report 2005-2016 was published. It says,

Veterans who use VHA have physical and mental health care needs and are actively seeking care because those condition s are causing disruption in their lives. Many of these conditions — such as mental health challenges, substance use disorders, chronic medical conditions, and chronic pain — are associated with an increased risk for suicide.

Interesting details

The veteran suicide rate is higher than that of the general public, particularly among women. As for methodology, firearms play a role more frequently in veteran suicides than among the general public. Out of every 20.6 suicides (the daily average), six of those individuals had recently used VA health care services and 11 had not. (Active duty personnel accounted for four a day.)

Counterintuitively, married veterans are at greater risk for suicide — possibly, very ill vets who are not getting all the medical support they need, and don’t want to be a burden on their spouses. Meaghan Mobbs wrote:

While rates of suicide were highest among younger veterans (ages 18-34) and lowest among older veterans (ages 55 and older), veterans ages 55 and older accounted for 58.1 percent of all veteran suicide deaths in 2015.

She went on to bring up very worrying possibility:

Furthermore, there is a strong body of evidence to suggest that suicide is contagious… With more social media use correlated with more depression, there is very real risk that veterans might feel they are not living up to their former lives, lives of their former teammates/buddies still in the fight, or the general idealized portraits that people tend to portray.

********

Watch this space for news of The Homecoming, the sculpture whose figures include a veteran.

Reactions?

Source: “Looking Up at the Bottom Line,” Amazon.com

Source: “VA reveals its veteran suicide statistic included active-duty troops,” Stripes.com, 06/20/18

Source: “VA National Suicide Data Report 2005–2016,” VA.gov, September 2018

Source: “The VA Releases Second National Suicide Data Report,” PsychologyToday.com, 08/28/18

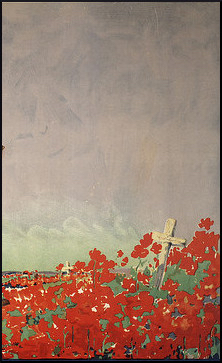

Photo credit: Toronto Public Library Special Collections on Visualhunt/CC BY-SA