In in 1989, in Austin, Texas, Richard R. Troxell, President of House the Homeless (HtH), started Legal Aid for the Homeless. His specialty is helping disabled people apply for the benefits to which they are entitled, because otherwise they don’t have a snowball’s chance in hell of getting off the streets. According to the latest HtH Annual Survey, more than half of Austin’s unhoused people are disabled to the point of being unable to work, so obviously, the need is enormous.

The application process often consumes a year, or even 18 months. If the effort succeeds, the Supplemental Security Income check is $735 a month — or a bit more than half the national minimum wage — which is in itself laughably, tragically inadequate.

With an income like that, the only kind of housing a person can possibly afford is subsidized. To be eligible for subsidized housing, a person must have some kind of income, and for a staggering number of Americans, this is the only kind they can get. Richard says:

I know who was the last family member that ever spoke to them and what year and what month that was. I know every demeaning job they ever worked at, or were abused at, or were robbed by the employer. I push them to try to participate in applying over and over again for housing that does not exist on pathways that we can now show are broken. Along the way, they quietly hate me. I push them very hard. All odds are are against our success.

In Austin, the housing crunch is especially brutal because of upcoming renovations that will affect people who live beneath bridges and overpasses. Many business and government figures had been under the impression that they had only to notify an agency that someone needed a place to live and poof! like magic, it would be done. What a misapprehension that was!

House the Homeless and other agencies are urging contractors to make use of the contingency funds attached to each infrastructure project to create transitional housing, and give the community time to catch up with the need.

A very real threat to mobile home parks

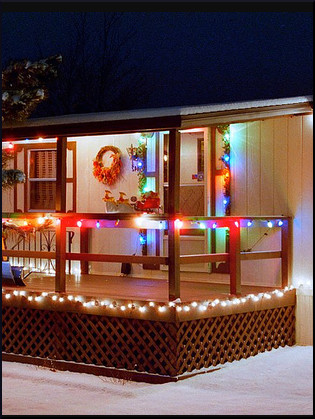

Austin’s affordable housing picture has become even more grim for a specific demographic. The residents of mobile home parks face not only code changes, but a consciousness on the part of speculators and developers that the urban land they occupy is a cash cow waiting to be milked.

These business people are unlikely to regard new, improved mobile home parks as a legitimate real estate sector. They want to build pricey condominiums and townhouses, and once they have decided to go that way, the process is rarely stoppable.

For renters, this is bad enough, because they will never find apartments as inexpensive. For people who own their mobile homes, the prospect of displacement is a nightmare. In the unlikely event that they find a new place to set up, the cost of moving such a structure is at least $5,000 — even more, in many cases, than the apartment-dweller’s moving expense of first and last months’ rent, plus security/cleaning deposit, plus truck rental.

The human element

Mobile home parks are often more than neighborhoods — they are villages, where relationships have grown and flourished over the years. When people are forced to relocate, their mutual babysitting and ride-sharing networks are shattered, friendships are fractured, and children are traumatized by school changes.

Some trailer parks still have RVs parked in them, where people actually live, and the likelihood of their being able to find a different spot to park is almost nonexistent. Altogether, changes in this ecological niche could potentially affect thousands of low-income residents.

According to researcher Gabriel Amaro, quoted in the article linked above, “Mobile home parks are the last bastion for affordability in Austin.” But very little importance is attached to their survival or continuing viability as an acceptable way to meet housing needs. Far-reaching adjustments are in the works, as the city overhauls its housing blueprint via a program called CodeNEXT.

Not just in Austin

These same problems exist in cities all over America, where housing costs eat up an increasingly large portion of family incomes, and every day more and more people face the specter of homelessness. Some complacent members of the housed population imagine the poor as privileged beings who have endless amounts of leisure time, so they should not mind jumping through a lot of procedural hoops. It gives them something to do and saves them from the threat of boredom, right?

In reality, this easy assumption could not be farther from the truth. For a mother of three who has just received an eviction notice, every phone call, every appointment, every official requirement is a monumental challenge. This fragile family might have the tremendous luck to be assigned a shelter room right away, but now there are even more necessary meetings.

Who is willing to watch the children, and can they be trusted? What if somebody is sick? How does she, or how do they, travel to the appointment? Does she have to carry food for the kids, and how will they behave while she has that all-important talk with the person at the counter or behind the desk? When they leave the office, will the ex-husband violate the restraining order and confront her?

A single person faces his or her own set of obstacles. Which of their belongings do they have to carry along, so they won’t be stolen? Is there any chance of getting a shower appointment the day before an important meeting?

What about their so-called criminal record, consisting of class C misdemeanor tickets for violating “Quality of Life Ordinances” that were enacted out of consideration for everyone’s quality of life but theirs? Even the federal Department of Justice gets it:

Needlessly pushing homeless individuals into the criminal justice system does nothing to break the cycle of poverty or prevent homelessness in the future. Instead, it imposes further burdens on scarce judicial and correctional resources, and it can have long-lasting and devastating effects on individuals’ lives.

In the homeless community, discouragement is widespread. Negative experiences pile up unrelentingly. It is easy to slip into hopeless apathy, the sensation that there is no point to anything. All over America, people in need feel like all they ever get are empty promises.

On the other side of that equation, even the staunchest advocates, the best and most highly motivated helpers, suffer from burnout. Eventually, their souls are scorched by the knowledge that they are unwillingly and unavoidably part of the monstrous fabric of lies.

A dedicated social worker can help people retrieve lost documents or fill out forms until the cows come home, as the old saying goes. But if the government has no money, or insists on spending what it has in useless ways, all the caring and trying amount to nothing.

Reactions?

Source: “Justice Department Files Brief to Address the Criminalization of Homelessness,” Justice.gov, 08/06/15

Source: “Mobile home parks at risk of redevelopment,” MyStatesman.com, 02/06/18

Photo credit: PJ Nelson on Visualhunt/CC BY-SA