Earlier this year, a Daily Kos columnist pointed out that, however many American service members died in the Vietnam war, twice that many Vietnam veterans are currently experiencing homelessness in the United States, for which they fought and are owed plenty. We have heard of “the gift that keeps on giving.” Vietnam was “the war that keeps on taking.” For these men and women, Southeast Asia is not ancient history. In fact, there are even veterans still around from before Vietnam.

Additionally, numerous veterans of more recent and ongoing conflicts are on the streets. They have all earned “sweat equity” in our country, or perhaps it should be called “blood equity.” Here is the quotation:

67,495 veterans are homeless on any given night and twice as many experience homelessness during a year.

The page consulted here gives a whole list of statistics, and these are two of the most pertinent ones.

23% of the homeless population are veterans

76% experience alcohol, drug, or mental health problems.

There are two different facets to look at. One is the accuracy of the various numbers. Popular Mechanics magazine published a very technical yet highly understandable article about why the numbers are problematic. Joe Pappalardo explains how current figures can lose their apparent meaning, because it is impossible to know whether the methodology obscures some deeper truth. He mentions an announcement that was made by HUD secretary Shaun Donovan, stating that veteran homelessness had decreased by nearly 12% in a year.

The journalist says of Donovan:

But what he didn’t mention is that between 2010 and 2011, HUD changed the way it counts homeless veterans, and those changes could throw uncertainty on the veracity of the numbers. Last year, HUD stopped using statistical estimates and instead mandated that homeless organizations that receive federal money survey homeless people to determine if they are veterans. They also used figures supplied by local Veteran Administration (VA) programs instead of estimates.

In time, of course, a change of technique becomes the new routine, and numbers are more reliable. But they are never entirely reliable. They are always, at best, estimates. Because so much of bureaucratic procedure depends on numbers, both the government agencies and the public would prefer accurate ones, but we make do with what we can get.

More important is the human story behind the numbers, and sometimes fiction can illustrate such things better than hard facts. In Michael Connelly’s novel The Black Echo, one character is a retired colonel who runs a group home for veterans released from jail. He says:

You know, these boys were destroyed in many ways when they got back. I know, it’s an old story and everybody’s heard it, everybody’s seen the movies. But these guys have had to live it. Thousands came back here and literally marched off to the prisons… I wondered what if there hadn’t been any war and these boys never went anywhere… Would they still have ended up in prison? Would they be homeless, wandering mental cases? Drug addicts? For most of them, I doubt that. It was the war that did it to them, that sent them the wrong way.

Los Angeles is the site of one of the most bitter and long-fought battles on the home front. Since 1888, America’s vets have owned 400 acres of prime real estate smack-dab in the middle of LA. The land contains the Veterans Administration hospital and outpatient clinics, and a whole pack of unrelated business tenants. The administration and the VA need to put that land to the use of the veterans, and build long-term supportive housing on it. All the bureaucrats are blaming each other for the lack of progress, and the American Civil Liberties Union has filed suit.

To renovate one (1) building to house the homeless, $20 million was allotted months ago. No construction contract has even been drawn up, but somehow a completely renovated building is promised by August of 2014. Gee, that’s only another year and a half — and it will only have 65 beds! Meanwhile, an estimated 8,000 veterans are on the streets of LA every night. Advocates are asking for at the very least, help in establishing a tent city on some of the land. But the prospects don’t look good.

A Housing Placement Boot Camp was, coincidentally, held in Los Angeles, to teach agencies how to shorten the time it takes (many months) to place a homeless veteran into housing. One suggestion is that nonprofit organizations obtain the inspection standards required by the local public housing authority, so they can get a jump on checking out prospective rental quarters. Also, it would help a lot if the minimum income requirements could be eliminated.

Several other recommendations, if followed, can speed up the process. One is that the individual’s military discharge form be considered as adequate identification, without requiring a birth certificate or social security card. The big one, which House the Homeless has discussed before, is that the “housing first” principle be followed. Since federal law doesn’t require a veteran to enter or complete substance abuse treatment before receiving a housing voucher, local VA branches should not require that. With a home base to work from, a recovering addict or alcoholic has a much greater chance of success. If the true goal is to help people clean up their act, “housing first” is the obvious course.

Reactions?

Source: “Helping Our Homeless Veterans,” Daily Kos, 10/26/12

Source: “How Does Washington D.C. Count America’s Homeless Vets?,” Popular Mechanics, 01/19/12

Source: “Homeless Veterans: Whose Responsibility?,” The New York Times, 10/08/12

Source: “Top 9 Things You Can Do Right Now from 100K Homes,” usich.gov

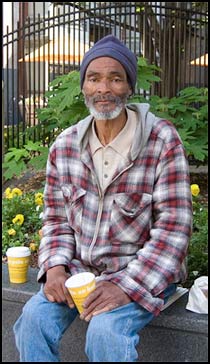

Image by sneakerdog.