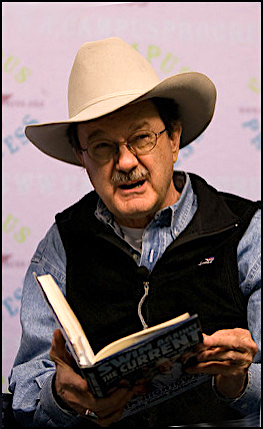

Pictured on this page is one of the smartest and most beloved Texans who ever shared thoughts with the world. His bio says,

National radio commentator, writer, public speaker, and New York Times best-selling author, Jim Hightower has spent four decades battling the Powers That Be on behalf of the Powers That Ought To Be — consumers, working families, environmentalists, small businesses, and just-plain-folks.

A ferocious caller-out of corporate misbehavior and governmental malfeasance, he runs The Hightower Lowdown, a website whose motto is “Everybody does better when everybody does better.” Hightower is what we now call an influencer or a thought leader; in other words, someone whose endorsement is worth being proud of.

He says this about Looking Up at the Bottom Line:

Finally, someone with some common sense! Troxell lays out a plan that will end homelessness for over 1,000,000 wage workers — without costing tax payers a dime. Plus, this is a great read — a compelling activist’s tale.

Looking Up at the Bottom Line is of course the book written by House the Homeless President Richard R. Troxell. The autobiographical volume tells how, after serving as a U.S. Marine in Vietnam, Richard returned disoriented, emotionally damaged, and without a place in American society, i.e., homeless. He tried some college, but it didn’t work out. When his father died, he says, “I went over the proverbial edge… I rejected people and began living in the woods.”

With only a backpack, Richard traveled to North Carolina, Louisiana, and New Mexico, sheltering in a truck and even a cave. He worked for the Forest Service, restoring trails, and in a bar, and as a volunteer firefighter. Canada seemed like a good idea, but somehow he ended up in Philadelphia instead, and that is where things changed. Living in an abandoned house, he met a fellow named Max Weiner, who set him on the road to political activism.

Deep in the heart of Texas

We’ll skip ahead to Richard’s eventual arrival in Austin, where he set out to challenge unfair housing regulations. This led to a course of working with (and when necessary, against) the city council, various political operatives, business interests, and the local authorities. In 1989 he co-founded the non-profit organization House the Homeless.

The struggle is on behalf of all the displaced and unhoused, but Richard could not and cannot help having a special place in his heart for ex-military people. He wrote,

We have veterans who have served our country well in Vietnam, Desert Storm, the Gulf War, Iraq and Afghanistan, killing in the name of God and Country, returning to their home only to find they have none. Others were so traumatized, like myself, that they vomited it all up and wandered the country aimlessly for years confused, in pain, and abandoned.

Harking back to his own Southeast Asia experience and its aftermath, he says,

It was a senseless war in which soldiers, myself included, were left unsupported at every turn in Vietnam and again when we returned home. The ones that it did not maim or kill, it made crazy and homeless for many years. Some are still that way. Most of these young men and women were too emotionally destabilized to work even if they could find it. Many were suffering from the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, PTSD.

He adds a poignant detail from that historical era, of which few Americans are aware:

Veterans of World War II scorned Vietnam veterans. Even though there was a Department of Veterans Affairs, it was comprised of WWII veterans and there was no outreach and no welcome mat for Korean and Vietnam veterans. World War II veterans had fought in a “real war.”

That was when increasing homelessness in the Homeland became glaringly apparent, with the national disgrace of placeless veterans living in alleys, sheds, wooded areas, tunnels beneath cities and even, with any luck at all, in shelters. It would not be surprising to learn that, over the years, VA hospitals have contained individuals who did not really need to be in medical facilities, but who would otherwise be homeless. A doctor’s compassion can stretch to finding reasons to delay a patient’s discharge.

With or without government aid, many vets have been able to reintegrate into society. But since Vietnam, the country has been in a constant state of war, so there is no shortage of newly discharged vets to take the place of those who have managed to achieve a stable lifestyle. Even today, the statisticians who keep track of these matters estimate that around one-third of people experiencing homelessness in the United States are veterans.

This explains why Austin’s Homeless Memorial Sunrise Service is always held within a week of Veterans Day. Richard’s story is similar to that of the fictional character John, one of the figures in the sculpture that will soon become part of the local landscape, and readers are enjoined to watch this spot for further news of The Home Coming.

Reactions?

Photo credit: Center for American Progress on Visualhunt/CC BY-ND