“Wait, what?” — is one thing that you’re apt to exclaim, when you can’t believe what you just heard. For instance, on being told that it could take nearly two years for the VA to make a decision about treating her physical disability or psychological problem, a veteran might say, “Wait, what?” — and then probably a whole lot of rougher words.

Coming “back to the world,” a male veteran might learn that he is an expectant father, when that is a biological impossibility. A veteran of either sex might return to find that the promised sweetheart gave up on waiting, and hooked up with his or her best friend. Anybody can come back and face the grim reality that their step-parent got tired of storing their few possessions, and pitched everything — music, high school yearbooks, civilian clothes — in the dumpster.

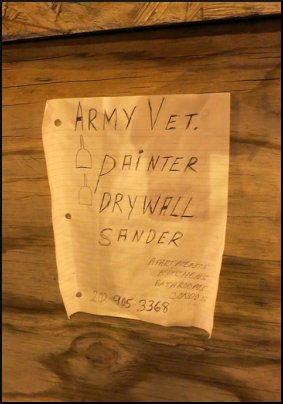

Although the government is very optimistic about “transferable skills,” anecdotal evidence to the contrary seems to pop up all over the place. We previously mentioned Matt Farwell, whose 4.5 years of military service “provided plenty of skills with no legal application in the civilian world.”

Even with an eminently useful specialty, the returning vet may find protectionist policies that require training as if from the very beginning, in order to be certified. And whether veteran or not, many people these days have learned that a minimum-wage job does not provide a living wage.

The “Wait, what?” reaction kicks in frequently for returning veterans who discover a series of unpleasant surprises in a place that is not the America to which they dreamed of returning. Meanwhile, during all this turmoil, something else might be going on, as Richard R. Troxell of House the Homeless suggests:

It is during that first year after discharge that the demons flood their minds and they relive over and over and over again the most horrific and unimaginable events of their lives.

Huge disconnect

If that isn’t enough to handle already, what if the person has a medical condition or an emotional breakdown? After initial contact with the VA system, the average wait, to resolve a first-time claim, is between 316 and 327 days. The latest figures finger Reno, NV, as the worst place, with an average time gap of 681 days. New York, at 642 days, is not far behind.

Normally, the things that tie a person to the world and prevent suicide are few and simple. A person wants to have the sense of belonging, and as if life has some purpose, or at the very least, to feel useful somehow. And the average person who isn’t a veteran probably avoids death and pain.

Now, the veteran. The average military member has formed very close ties to other members of the unit, especially in combat. Back in the USA, that sense of belonging is gone. Faced by unemployment or underemployment, especially if unable to find a place to live, a person is likely to feel useless. Live or die, it makes no difference to the world. And having gained a tolerance for pain and a close acquaintance with death, a person might lose inhibitions about those conditions. In a mental state like this, suicide looks like a viable alternative.

The real costs of war

Some are discarded and forgotten; some are simply beyond the point of being able to accept even the most generous and well-meaning help. Either way, veterans who take their own lives make up a big portion of the real cost of war, and it’s difficult to get a clear perception of just how many such lost souls there are. Turn the clock back five years, to a news item about the same bureaucrat who said “Suicide occurs just like cancer occurs”:

William Feeley, the Veterans Health Administration’s deputy undersecretary for health for operations and management, said in an April 9 deposition that VA did not have a metric to track suicides or attempts. He added that he could not recall a time since he took office in February 2006 when VA had conducted a quarterly review of suicides or attempts…

The VA started to focus on suicide prevention in 2007, but only through connection with its own hospitals and clinics. Statistics were not a huge concern. In 2010, VA Secretary Eric Shinseki asked for cooperation from the governors of every state in getting suicide data on veterans outside the Veterans Administration health care system. Problems with access to data contained in the National Death Index needed straightening out. VA records needed to be melded with those of the Department of Defense, and there were yet more numbers to obtain from the Veterans Crisis Line and Suicide Behavior Reports. The project is underway, but as we will see next time, the system hasn’t caught up yet.

(To be continued…)

Reactions?

Source: “Back in the World — Homeless Veterans,” HouseTheHomeless.org, 05/14/13

Source: “Over 600,000 veterans caught in messy bureaucracy awaiting pending claims,” NYDailyNews.com, 05/07/13

Source: “VA Official Says veterans’ suicides not reflection of agency negligence,” GovExec.com, 05/05/08

Source: “Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services Suicide Prevention Program,” VA.cov, 2012

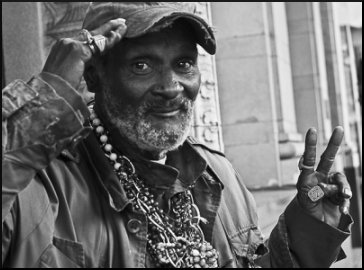

Image by weStreet (Werner Schutz).