April 1 is the National Day of Action for Housing. It is a Saturday, and what a person might very usefully do if at all possible, is travel to the nation’s capitol for a rally and overnight vigil at the National Mall.

Supporters are encouraged to bring tents, signs, families, and friends. The Day of Action is meant to create temporary tent cities, to call attention to the housing crisis, the healthcare situation, the ever-increasing criminalization of poverty and homelessness, and the racial inequality inherent in all of these.

But if a trip to Washington, D.C., is out of the question, do not despair. Many other cities are also observing the event. If one is not near you, consider becoming a local organizer. Now would be a great time to start planning what is called a sister action event for next year, and the National Coalition for the Homeless will help.

Their nine-page pamphlet (PDF) titled “National Day of Action for Housing Media Toolkit” includes Talking Points and Tips; Frequently Asked Questions; Social Media; Press Release; and Contact Information. When framed in terms of goals, the Day of Action objectives include:

Preserving and creating housing funding on local, state and national levels for low to moderate income households in particular… Foreclosures and limited housing assistance contribute to the increase in homelessness among the low-income families in particular.

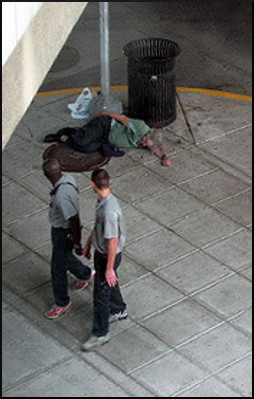

Stopping ordinances and practices that criminalize the unhoused, promote racial discrimination, and prevent equal treatment of immigrants and the LGBTQ community… These ordinances include criminal penalties that may prevent those in need from receiving housing and social services. The penalties are doled out for violation of such life-sustaining activities as eating, sitting, sleeping in public places, camping, and asking for money.

Promoting access to emergency housing, employment, food assistance, and healthcare for all Americans in need… Poor health is big contributing factor to homelessness, as both a cause and the result. Exposure to elements, violence, stress, addition, mental health conditions, and other serious conditions that require regular treatment are contribute to the problem.

Homelessness Myths

This is a good time to look at the collection of homelessness myths collated by journalist German Lopez for Vox.com.

An Urban Institute survey found that more than 40% of homeless people they questioned were likely to have done some paying work in the month previous to the survey. Homeless adults in families are regarded in some ways as being in a class by themselves, because of the responsibility for others beside themselves. A Housing and Urban Development study found that 17% of homeless adults in families actually had paying jobs at the time of the survey, and that over half of the people questioned had worked during the previous year.

This leads naturally to the existence of another myth, the belief among allegedly sane Americans that having a job means that a person can afford a place to live. Name a state, any state, and the unfortunate truth is that a person with a full-time minimum-wage job can’t afford to rent an apartment. House the Homeless offers plenty of material addressing this problem.

Some housed people think that homelessness is always forever, but in actuality, only one in six people experiencing homelessness are classified as “chronic.” Sometimes this is related to mental illness, and the number of people who turn up with previously undiagnosed and untreated traumatic brain injury is shocking.

One of the big myths is that homelessness exists only in the interiors of large urban environments, which is simply not true. In fact, slightly less than half of America’s homeless people are in big cities. However, the big-city numbers are growing disproportionately. People think that alleviating homelessness is a federal budget-breaker, but compared to a lot of other, less urgent problems, government spending on homelessness is paltry.

Lopez’s last paragraph is the best, and addresses Myth #11, that fighting homelessness is expensive. Not when compared to the alternatives:

Studies show that simply housing people can reduce the number of homeless at a lower cost to society than leaving them without homes. The Central Florida Commission on Homelessness found housing costs $10,000 per person per year, while leaving them homeless costs law enforcement, jails, hospitals, and other community services $31,000 per person per year.

Reactions?

Source: “National Day of Action for Housing Media Toolkit,” NationalHomeless.org, 2017

Source: “11 myths about homelessness in America,” Vox.com, 09/23/15

Photo credit: Doug Waldron via Visualhunt/CC BY-SA