When the Super Bowl took place in Minneapolis earlier this year, the city seems to have made an effort to minimize the trauma experienced by people experiencing homelessness. Officials explained that street people were steered away from the central festivities — not to hide their existence, but because the massive crowds and heavy law enforcement presence could be problematic for them. The police and the event’s 10,000 volunteers received training on how to direct needy people to resources.

Westminster Presbyterian Church, in the heart of the affected area, opened a space for people to store their belongings in the daytime, and served coffee and a bag lunches. Over the weekend, shelters for single adults expanded their hours.

Some train lines required possession of a Super Bowl ticket to ride, and indoor public spaces were made unavailable. The routes people customarily take from Point A to Point B are the fastest, most direct routes, to avoid being out in the cold any longer than necessary. But changes in transit routes, and the closing off of downtown areas, made it extra difficult for street people to get around.

Journalist Solvejg Wastvedt wrote:

For Minnesotans with the fewest resources, a Super Bowl in subzero weather can be more than a minor disruption. Some of downtown Minneapolis’ homeless residents say the changes there are straining their coping skills.

Because the hotel rates increased so much, the public money that usually shelters some families was not enough to keep them under a roof. Raz Robinson wrote:

Many of the 2,000 homeless children in the St. Paul public school system had to sleep with their families in tents, cars, or simply outside on the street.

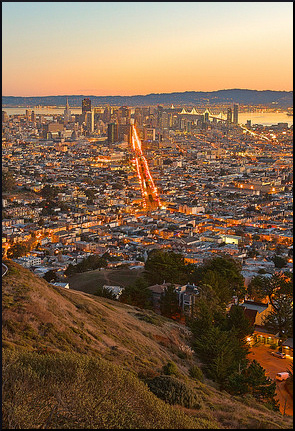

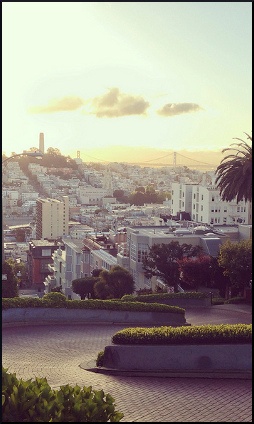

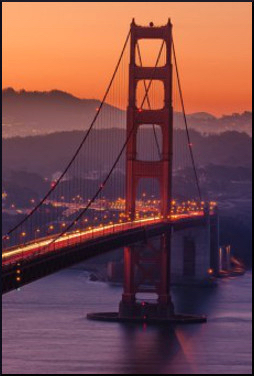

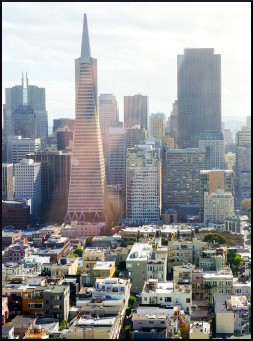

Still, the city did not engage in the sort of mass displacement tactics that had characterized the preparation for the big game in San Francisco two years before. In the past, Minnesota has not been so tolerant. Reporter Kelly Smith recalled how the police had swept away homeless camps for an all-star baseball game in 2014 and for the Republican National Convention in 2008.

Brotherly love

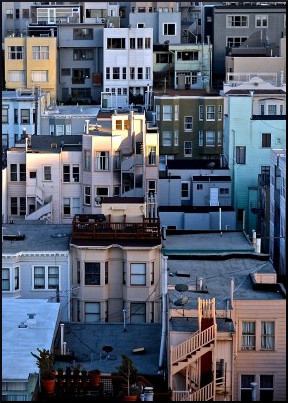

In the summer of 2016, highway construction and park renovation caused about 50 people to wind up sleeping on the grounds of Philadelphia’s Convention Center, with the Democratic National Convention coming up. At the time, the city had around 14,000 units of emergency and long-term housing, with the permanent housing always full, shelters and safe havens generally 90% full, and about 700 people routinely on the streets.

It must be admitted that some people are unable or unwilling to enter shelters, and that’s just how things are. Still, there is always need, and the city budgeted around $60,000 for 100 extra temporary beds during the convention.

“Most Cities Evict Their Homeless Before Big Events. Philly Is Trying Something New,” read the ThinkProgress.org headline for a story by Bryce Covert. He wrote:

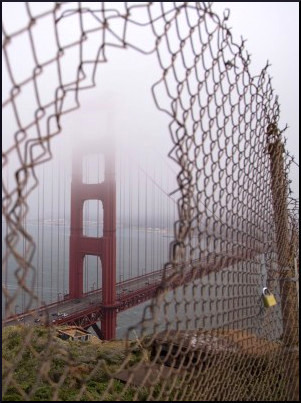

When San Francisco hosted the Super Bowl in February, it relocated homeless people from particular areas, with some homeless people reporting that their belongings were confiscated, and while it said it would give them slots at a shelter, the shelter already had a huge waiting list.

When the Pope came to visit New York City, the city swept nearby homeless encampments and threatened to ticket and arrest anyone who didn’t leave. Before hosting the Republican National Convention last week, Cleveland, Ohio enacted new restrictions that effectively criminalized being homeless near the convention center.

In anticipation of the convention, Philadelphia reverted to its own, more compassionate and satisfactory Pope visit plan, concentrating on outreach efforts, and those 110 (or 110) additional beds.

A permanent feature that was created for the occasion but remains active and extremely helpful is Food Connect, an app that garnered about 7,000 meals for people experiencing homelessness, from the bounteous amount of food unused during the convention events.

Reactions?

Source: “Super Bowl disruptions more than just annoyance for Mpls. homeless residents,” MPRNews.org, 02/04/18

Source: “Super Bowl Fans Accidentally Put Homeless Minnesota Kids on the Street,” Fatherly.com, 02/05/18

Source: “Where did the homeless go in Minneapolis during Super Bowl week?,” StarTribune.com, 02/01/18

Source: “Uh-oh! Company’s coming. Get those Philly homeless out of sight,” Philly.com, 07/03/16

Source: “Most Cities Evict Their Homeless Before Big Events. Philly Is Trying Something New,” ThinkProgress.org, 07/25/16

Source: “New Beds for Homeless, Food Rescue App Ensure Lasting Impact of DNC on City’s Most Vulnerable,” NBCPhiladelphia.com, 07/28/16

Photo credit: Leif Kurth (26.3andBeyond) on Visualhunt/CC BY