Our Mission

Founded in 1989, HtH is the oldest all volunteer, action, homeless organization in the state of Texas. The mission is Education and Advocacy around the issues of ending and preventing homelessness.

Urgent Issues

Re-Criminalizing Homelessness — Speak up now!

HtH supports the direction being taken by the City of Austin’s relatively new Homeless Strategy Office, led by a very committed and responsive David Gray, and with the commitment of Charles Loosen and other staff. We further strongly advocate ALL positions below that preceded The vote to basically criminalize homelessness — especially:

reinstating a camping ban must consider that those with disabilities, the aged, and in fact anyone with no place to go. The no sit/no lie ordinance is absolutely inhumane and unconscionable we must have at least 15 minute respites particularly for those with disabilities and make other provisions.

Mayor Kirk Watson, elected in 2023, is working to secure funding for homeless services from the State and within the City Budget.

2025 interests:

City Council approved a resolution making homelessness a top financial priority.

Increase the capacity of the Homeless Strategy Office to address and implement a comprehensive approach to strategic advancements in homelessness response. (Plan detailed in a 50-page memo from David Gray, June 2025).

Examples:

1. Expand HOST (Homeless Outreach Street Team) support including team members:

APD officers, EMS paramedics, behavioral health clinicians, social workers, peer support staff.

2. Support for Marshaling Yard operations.

3. Rapid Response housing and safe housing, especially for families.

4. Increase shelter beds with support; and more.

The Austin city council recently voted to put on its May 2021 ballot a vote to reinstate the no camping ban including the no sit/no lie ordinances. Now is the time to contact your mayor and council members particularly those who have supported decriminalizing homelessness, such as Mayor Adler, Kathy Tovo, Ann Kitchen, Greg Casar, Sabino Renteria, and others, we pray.

First call to action is cold weather shelter. Anyone that reads this, our urgent plea is to email our mayor and city council in this urgent time of cold weather. House the Homeless is encouraging to use the Convention Center or other alternatives sites that are already over burdened due to Covid-19 or at capacity.

A second call to action is to not displace unsheltered neighbors from bridges and the four major camp areas without having an immediate plan for alternative shelter/housing.

Finally, advise your mayor and council members that the wording for the May ballot regarding reinstating a camping ban must consider that those with disabilities, the aged, and in fact anyone with no place to go. The no sit/no lie ordinance is absolutely inhumane and unconscionable we must have at least 15 minute respites particularly for those with disabilities and make other provisions.

Federal Minimum Wage Debate

Federal resolve is insufficient; highly recommend Universal Living Wage formula indexed on the cost of housing wherever the person lives and works.

April 2017 “Mighty Homeless” Serenade Diners in Advocacy Effort

Spring Happenings

The National Day of Action for Housing took place this year on April 1, and was covered for Austin’s American Statesman by Elizabeth Findell on the front page of the Metro section. (The picture on this page is by Sue Watlov Phillips, in Washington DC.)

In Austin, a group of awareness-raisers carried signs and serenaded shoppers and diners along South Congress Avenue, bowing after their chants concerning affordable housing. They shook some hands, and passed out flyers explaining how 25 cities, including Washington, D.C., joined in holding rallies and teach-ins on the day.

Philosophical underpinnings

Speaking of Washington, many concerned people have noticed that among all the verbiage proceeding from the nation’s capital since the new administration moved in, the word “homelessness” has been notably absent. Yet this is a huge and horrible domestic issue. When coupled with other current trends, like defunding health care and de-staffing the VA and releasing police forces from their already scanty restraints, homelessness just might get worse before it gets better.

We tend to naively assume that the taxes we pay will take care of all this stuff. Yes, we are correct in believing that those funds ought to be used to alleviate societal problems like hunger, homelessness, sickness, ignorance, and so forth.

But… We have to face the fact that this is not happening to anywhere near the extent that it should. The dollars we put into the system are not being converted into help for the people in desperate need. The awful truth is that we are all called upon to make more contributions of money, time, attention, self-education, and compassion. It’s the only way we will make it through these times.

Back to Austin

The Statesman website offers a slide show of a dozen photos of the event. Attendees included The Challenger Street Newspaper journalist Jennifer Gesche in a mechanical wheelchair. Many of the participants were individuals suffering from traumatic brain injury (TBI) or chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and House the Homeless President Richard R. Troxell has been working with them to secure disability benefits, successfully in seven cases so far, with four more still in progress.

Richard says:

I explained to the guys that they were Ambassadors for all the other homeless folks who could not be with us today, and to smile. Before they knew it, they were smiling for real. People could feel our power and sincerity. Everyone had a good old time, with warm feeling all around. They felt appreciated and cared about. Some told me they ended the day with hope…

House the Homeless has many messages, including the suggestion that Austin needs a workers’ hotel, a single-room occupancy establishment with shared facilities to keep the rent really low. A higher minimum wage would help, as well as more reasonable rental options.

Predictably, in the Statesman‘s comment section, someone asked, “Why don’t the homeless get a job?” This person obviously skipped the paragraph that reports, “Troxell said about half of the nation’s homeless people spend at least part of each week working.”

As always, House the Homeless urges people to learn about and support the Universal Living Wage, the idea whose time has come; the concept to prevent homelessness at its core. Call up the page and see how employers actually save money by paying a living wage — how, in fact, a living wage is good for not only for workers, but also for business owners.

How easy it is for an employer to have a team of valuable assets rather than reluctant, resentful workers who feel exploited and unappreciated! “With a long-term crew of capable workers, training costs are reduced, and experienced employees make fewer dangerous and expensive mistakes. There is less unscheduled absenteeism, and appreciably less internal theft,” Richard says, and a great many other eminently sensible things besides.

We also recommend his white paper, “Livable Incomes: Real Solutions that Stimulate the Economy.” For in-depth information about all these topics and more, please see Richard’s book, Looking Up at the Bottom Line. It chronicles an amazing array of activism, explains why many things in America do not work quite as they should, and offers numerous excellent ideas for fixing those things.

Demonstrate on Tuesday, April 18

If employers paid a fair living wage, the taxpayers would not be called upon to share so much of the burden of need. For instance, if employers paid a fair living wage, at least some fraction of people who now need food stamps would not, and, of course, people who are now homeless would be able to get themselves under roofs. Not all of them — but at least some. And that would be a vast improvement over the situation as it now stands.

To get fired up, see Richard’s 2011 Tax Day appeal. Make some signs and banners and get on down to your local post office to make a show, and remember:

Livable Incomes are the Gateway to Affordable Housing. — Richard R. Troxell

Reactions?

Source: “‘Mighty homeless’ serenade South Austin diners in advocacy effort,” MyStatesman.com, 04/01/17

Image: National Day of Action Group Cheer by Sue Watlov Phillips

Odd Jobs

Recently, House the Homeless looked at the situation in Washington, D.C., where shady contractors pit people experiencing homelessness against evictees (i.e., the newly homeless), and it’s ugly.

In any city, there are bound to be a few jobs specially allotted to, or created by, those who are out of options. The viability of a career in recycling depends on local ordinances; access to a buyer; having a way to store and transport the merchandise; and other factors.

California’s recycling rules have been in effect for almost 30 years, and for many street people, their only income derives from bottles and cans. In San Francisco, a person might make between $15 and $35 per day, depending on good weather, good health, and good luck in not having their haul stolen by competitors. There used to be 30 redemption sites and now are only two, very close to each other geographically, so people in any other part of the city have a hard time.

Waste management expert Martin Medina estimates that about 1% of the earth’s urban dwellers (about 15 million people altogether) live by harvesting society’s castaway materials. In some places their activities are, of course, criminalized.

For CommonDreams.org, Jack Chang wrote a respectful tribute to the trash pickers of the world:

Every day, they rescue hundreds of thousands of tons of material from streets and trash dumps that get reprocessed into all kinds of products. That not only cuts back on the resources used by industries but also lightens the load on dumps that are quickly reaching capacity.

“Urban Tactics; Nabbing the Elusive Nickel” by Saki Knafo is a still very relevant description of the world of “canners” in New York City a decade ago.

Hired feet

In 2012, for The Huffinton Post, Arthur Delaney described the activities of the Mid-Atlantic Regional Council of Carpenters which hired the homeless in Washington, D.C., for $8.50 an hour, to carry picket signs and raise their voices in chants. Critics decried a “cynical use of homeless people to do this dirty work.” The union seemed out of patience with anyone who questioned this hiring practice. Its members were busy at their jobs, and besides, the method had already been deployed in seven other cities.

From one of them, only the previous year, Joel Gehrke had reported this story:

In Grand Rapids, Mich., the Michigan Regional Council of Carpenters has started protesting companies that hire a local non-union carpentry firm, Ritsema Associates. Where does the union get its picketers? It hires them from a homeless shelter that is supported by Ritsema Associates.

So it gets very complicated and, as temp jobs go, picketing is in a whole different class from trash recovery. People experiencing homelessness also have been employed to count other people experiencing homelessness.

Some entrepreneurial individuals carve out highly idiosyncratic paths. Remember when Ted Williams, the “man with the golden voice,” was rediscovered and became for a short while an outsider celebrity? His former tent-mate offered Williams’s leftover cardboard signs for sale on eBay.

Reactions?

Source: “How Homeless Recyclers Make a Living Redeeming Recyclables,” PBS.org, 05/13/16

Source: “Scorned Trash Pickers Become Global Environmental Force,” CommonDreams.org, 03/25/08

Source: “Urban Tactics; Nabbing the Elusive Nickel,” NYTimes.com, 07/09/06

Source: “Paid To Protest, Some Homeless Almost Make A Living,” HuffingtonPost.com, 11/24/12

Source: “Union hires homeless picketers — and it gets better,” SFExaminer.com, 02/17/11

Source: “Homeless Count or Are Counted,” LATimes.com, 01/27/05

Image: Otterman56 (Ed)

The National Day of Action, and Some Myths

April 1 is the National Day of Action for Housing. It is a Saturday, and what a person might very usefully do if at all possible, is travel to the nation’s capitol for a rally and overnight vigil at the National Mall.

Supporters are encouraged to bring tents, signs, families, and friends. The Day of Action is meant to create temporary tent cities, to call attention to the housing crisis, the healthcare situation, the ever-increasing criminalization of poverty and homelessness, and the racial inequality inherent in all of these.

But if a trip to Washington, D.C., is out of the question, do not despair. Many other cities are also observing the event. If one is not near you, consider becoming a local organizer. Now would be a great time to start planning what is called a sister action event for next year, and the National Coalition for the Homeless will help.

Their nine-page pamphlet (PDF) titled “National Day of Action for Housing Media Toolkit” includes Talking Points and Tips; Frequently Asked Questions; Social Media; Press Release; and Contact Information. When framed in terms of goals, the Day of Action objectives include:

Preserving and creating housing funding on local, state and national levels for low to moderate income households in particular… Foreclosures and limited housing assistance contribute to the increase in homelessness among the low-income families in particular.

Stopping ordinances and practices that criminalize the unhoused, promote racial discrimination, and prevent equal treatment of immigrants and the LGBTQ community… These ordinances include criminal penalties that may prevent those in need from receiving housing and social services. The penalties are doled out for violation of such life-sustaining activities as eating, sitting, sleeping in public places, camping, and asking for money.

Promoting access to emergency housing, employment, food assistance, and healthcare for all Americans in need… Poor health is big contributing factor to homelessness, as both a cause and the result. Exposure to elements, violence, stress, addition, mental health conditions, and other serious conditions that require regular treatment are contribute to the problem.

Homelessness Myths

This is a good time to look at the collection of homelessness myths collated by journalist German Lopez for Vox.com.

An Urban Institute survey found that more than 40% of homeless people they questioned were likely to have done some paying work in the month previous to the survey. Homeless adults in families are regarded in some ways as being in a class by themselves, because of the responsibility for others beside themselves. A Housing and Urban Development study found that 17% of homeless adults in families actually had paying jobs at the time of the survey, and that over half of the people questioned had worked during the previous year.

This leads naturally to the existence of another myth, the belief among allegedly sane Americans that having a job means that a person can afford a place to live. Name a state, any state, and the unfortunate truth is that a person with a full-time minimum-wage job can’t afford to rent an apartment. House the Homeless offers plenty of material addressing this problem.

Some housed people think that homelessness is always forever, but in actuality, only one in six people experiencing homelessness are classified as “chronic.” Sometimes this is related to mental illness, and the number of people who turn up with previously undiagnosed and untreated traumatic brain injury is shocking.

One of the big myths is that homelessness exists only in the interiors of large urban environments, which is simply not true. In fact, slightly less than half of America’s homeless people are in big cities. However, the big-city numbers are growing disproportionately. People think that alleviating homelessness is a federal budget-breaker, but compared to a lot of other, less urgent problems, government spending on homelessness is paltry.

Lopez’s last paragraph is the best, and addresses Myth #11, that fighting homelessness is expensive. Not when compared to the alternatives:

Studies show that simply housing people can reduce the number of homeless at a lower cost to society than leaving them without homes. The Central Florida Commission on Homelessness found housing costs $10,000 per person per year, while leaving them homeless costs law enforcement, jails, hospitals, and other community services $31,000 per person per year.

Reactions?

Source: “National Day of Action for Housing Media Toolkit,” NationalHomeless.org, 2017

Source: “11 myths about homelessness in America,” Vox.com, 09/23/15

Photo credit: Doug Waldron via Visualhunt/CC BY-SA

Brain Injury Awareness Day Is March 22

In Washington, D.C., Brain Injury Awareness Day will be observed by a series of events organized by the Congressional Brain Injury Task Force, and specifically by its co-chairs, Rep. Bill Pascrell (D-N.J.) and Rep. Thomas Rooney (R-Fla.).

Earlier this year, House the Homeless sent an open letter to the administration in the nation’s capitol, presenting its 5-Year Plan for veterans as the top item on the agenda. It contained a shorter version of the information presented by Richard R. Troxell’s “Traumatic Brain Injury — A Protocol to Help Disabled Homeless Veterans within a Secure, Nurturing Community” and of the arguments set forth in that document. It tells the story of the 2016 survey carried out by HtH, and of what the organization’s consciousness of TBI has developed into.

How does the problem originate?

In theory, there should be no reason for military veterans to be jobless or homeless. These are people who were competent enough at life to be inducted into the armed services in the first place, and who were trained for one of the many types of jobs needed in the service, and who fulfilled the obligation they signed up for. In theory, veterans are the last people who should be wandering the countryside or the urban streets without anywhere to live.

As a general matter, approximately half the total homeless population in the United States is made up of people who are able to work but who lack jobs and affordable housing. The other half is made up of people who can’t work because of disability. Of that number, a great many are veterans. The disabilities that afflict them are chiefly due to TBI. Shockingly, the traumatic brain injuries they suffered go mainly unrecognized and undiagnosed.

The mystery of veteran homelessness is easier to understand when TBI, or traumatic brain injury, is taken into account. By now, most of the world understands the implications of Shaken Baby Syndrome, and, in many places, violently shaking a baby in a way that can cause brain damage is recognized as an aggressive act deserving of criminal consequences. What people tend to forget is that adults are also vulnerable to the chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) that can result from such injury to a human being of whatever age.

What can be done?

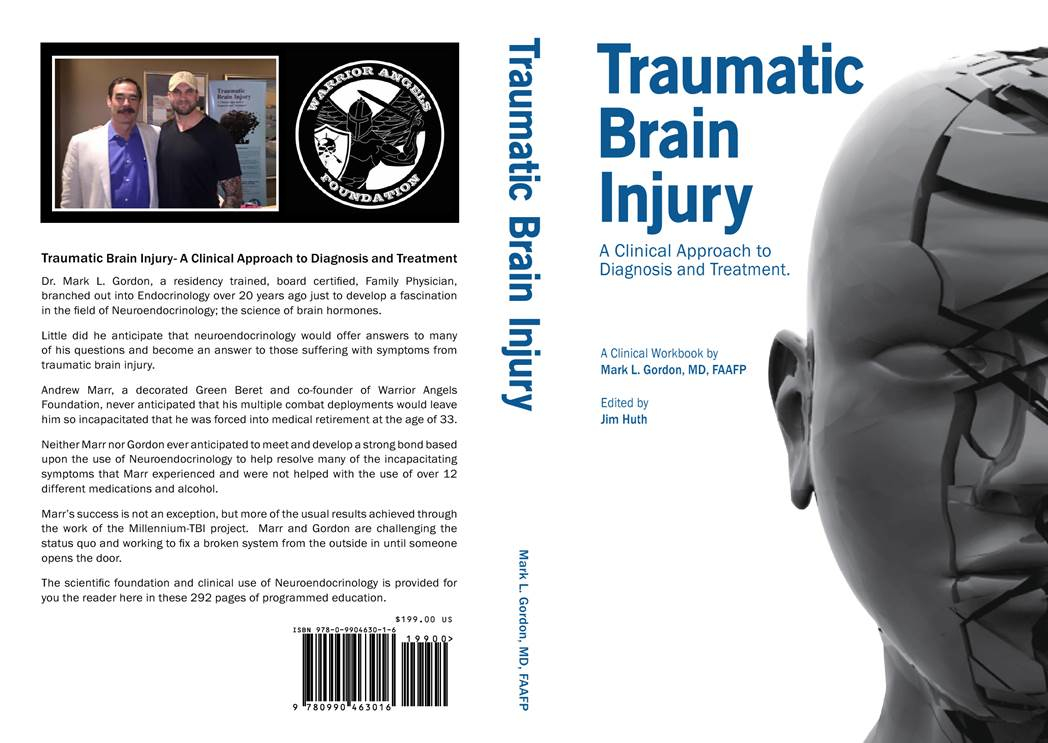

For a detailed yet understandable explanation of the whole subject, an excellent resource is an illustrated guide written by Dr. Mark Gordon, the pioneer of the field. Here we learn that traumatic brain injury is usually not diagnosed at the time it occurs; sometimes diagnosed years later when it has ripened into CTE, and often never recognized at all. The progressive degenerative condition is responsible for many physical and mental health problems that are misdiagnosed or blamed on a lack of personal responsibility.

Often, untreated TBI contributes to the astonishing statistics that tally suicides committed by veterans. In 2009 the Pentagon announced that according to their own estimate, as many as 360,000 veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts were walking around with traumatic brain injuries.

Troxell’s Open Letter says of Dr. Gordon:

Now he has crafted a medical protocol using human hormones to positively affect TBI. When asked, he has framed program success in this manner, “Out of 98 affected Veterans, we have had between 50 and 100% reduction of the symptoms displayed.” This is both astonishing and medically dramatic when looking at the range of symptoms involved. Realize that reduction of just one of these symptoms has life changing results.

The Millennium TBI Project, Warrior Angels Foundation, House the Homeless, Inc., HTH, are now collaborating with Alan Graham at Community First! Village, a 51 acre facility in Austin, Texas, where a 10 member homeless Veteran model project will assess and treat their brain injuries.

The complete story of these organizations’ effort is contained in “Traumatic Brain Injury,” mentioned at the beginning of this post. Four powerful and determined groups have banded together to break through the national brain fog that seems to surround this issue, and to make life-changing and life-saving differences for people affected by TBI, especially if they are veterans, and especially if they are homeless.

Please take advantage of the consolidation of so much important information, and consider donating to the continuation of these crucial efforts. A good place to do that is through Warrior Angels, a non-profit organization founded and run by combat veterans for the sole purpose of treating TBI.

Reactions?

Source: “Traumatic Brain Injury: A Clinical Approach to Diagnosis and Treatment,” TBIMedLegal.com, 2013

Image courtesy Dr. Gordon.

Learning From the 2017 Police Survey

Concurrent with the annual Thermal Underwear Drive party for people who are experiencing homelessness, House the Homeless (HtH) has established a splendid tradition — the annual survey. The guests are offered the opportunity to share their thoughts on a particular topic. Past subjects have included work, sleep; Traumatic Brain Injury, and other medical issues.

Most often, unhoused Americans struggle with at least one major life problem. For instance, even someone who was in pretty good shape when they hit the streets will probably not stay healthy for long. Sleep deprivation is difficult to take seriously until one has personally suffered from it for several nights in a row. Among homeless people, the “age acceleration” effect is real.

The answers contributed by the survey participants are wonderfully helpful for discovering the most effective ways of assisting people to get their lives back on track. The information is collated and commented upon, and sent to people and institutions both in Austin and around the USA. In the best-case scenario, facts from the HtH Surveys will help guide policymakers.

Written by HtH President Richard R. Troxell, the introduction to the report on the 2017 Police Survey says:

Each of the ten questions in the survey include comments that are intended to enhance the readers’ understanding of the implications of each question.

This survey documents the increasing criminalization of homelessness. It seems that relations with “the system” are a top-priority topic, because it was previously addressed only two years ago. This proximity in time allows for some alarming comparisons. For instance, over those 24 months, the number of women experiencing homelessness in Austin has increased by 28%.

One question is particularly significant in light of Austin’s No Sit/No Lie ordinance, which HtH helped design with the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) in mind. It reads like this:

5) Has a Police Officer ever given you a ticket for sitting or lying down even though you told them you were disabled or too sick to move?

Also crucial is a new question that had not appeared on the 2015 survey:

5a) Have your Class C misdemeanor tickets (No Sit/No Lie, No Camping, etc.) ever been barriers to getting a job or housing?

Twenty-eight percent of the people experiencing homelessness in Austin said that yes, Class C misdemeanor tickets had interfered with their ability to obtain work or housing. Let that sink in for a minute. Even government programs that are meant to help the homeless may balk at people with “criminal” records, which is cruelly ironic when the government itself creates the relevant offenses by criminalizing such acts as sitting a sidewalk. It is almost as if “the system” intentionally sets out to manufacture reasons to refuse help to destitute citizens.

And even when it issues housing vouchers, the government can’t force landlords to accept tenants with “criminal” records. What is the point of proscribing acts which unhoused people can not help but commit? In what universe does it make sense to exacerbate the problems of people who are already so thoroughly disadvantaged?

To Question 5c, almost an equal number survey participants (27%) answered N/A, or “not applicable.” These are people who are too disabled to work or even to seek housing; people who have given up; people who have not gotten close enough to applying for either work or housing for the question to even matter.

The seventh question brings to light a barbarous practice that is not supposed to happen at all:

7) Have you ever had your ID taken by police and not returned?

Twenty-nine percent of the respondents, or 74 individuals, answered yes to this — a total slightly better than the 33% two years ago.

Nevertheless, Richard says:

[…] this is still completely unacceptable as replacing photo ID is very costly in terms of both time and money. Remember, these people are homeless. They are indigent. All social services in Austin require photo identification, so to be left without photo ID only acts as an additional barrier to escaping homelessness.

Here is another disturbing question, and the replies are even more disturbing:

8) Have you ever had your things taken by police without giving you a receipt and the name of a contact person to get your things back?

Thirty-six percent of the people said yes, which is well over one-third. Imagine that. People who already have next to nothing are vulnerable to having even that small bit confiscated by law enforcement officers, and there is no recourse. As Richard puts it, they “are having all of their medications, prescriptions, and important papers taken and never returned.”

He is also quite clear about a thing that apparently happens a lot. A person is ticketed and told to show up in court on a certain date, and then when they show up, they are told that their ticket “is not in the system yet.” So they have to return, maybe more than once. Thirty-seven percent of the people said it had happened to them. Richard’s reaction is:

Any action that causes people experiencing homelessness to make multiple trips to the court system to prevent a ticket from “going to warrant” that leads to their arrest is detrimental to their existence and simply an additional barrier to their escaping homelessness.

Reactions?

Source: “2017 Police Survey,” HouseTheHomeless.org, 2017

Photo credit: orangeaurochs via Visualhunt/CC BY

Annual Survey – This year HTH looks at the relationship between citizens experiencing homelessness and the Austin Police Department that works to protect and serve them.

Not Every Job Is an Opportunity

In Washington, D.C., a person experiencing homelessness can climb into a van and drink some cheap alcohol he thinks is free, but which later turns out to be deducted from his pay. His pay for what? For helping as many as two dozen other men evict a family. This overstaffing is for the sake of speed.

Elizabeth Flock explains:

[…] because in D.C. evictions are overseen by the U.S. Marshals Service, which has other jobs to do — that crew must be large enough to quickly carry out the eviction.

Imagine being a kid in the only home you know, the house your parents rent. All of a sudden, 25 strange men show up, plus a number of Marshals (possibly with guns drawn). The invaders are all over the place, taking your stuff out to dump on the sidewalk, and pushing you out along with it.

The situation is lousy for the workers, too. They get into that van without knowing how long their work day will be, but with a fair certainty that nobody will be serving any food or water. It’s a “bring your own gloves” gig. Flock says the trucks are not equipped with dollies or other normal moving amenities, and if a worker gets hurt, that’s just tough luck.

Bruised or intact, there is no guarantee that the men will be returned to the starting point. They may be left stranded miles away from their home base. The promised pay might be as little as $7 for the entire day, and there’s a good chance the company will stiff them. In return for no background check or request for credentials, that’s the kind of job you get.

However, throwing people out does offer plenty of opportunity to steal from distressed ex-tenants, along with the chance to mistreat a vulnerable population, and most people quite frankly don’t need that kind of temptation laid in their path.

How it goes in our nation’s capitol

The concept of fair labor practices isn’t even a blip on these companies’ radar. The bosses allegedly engage in price-fixing. The going rate for this type of day labor used to be almost three times as much. Now the supply of destitute workers is much greater than the demand for their rudimentary services, and the workers are badly in need of cash, perhaps to feed habits.

A large law firm supported a class-action suit, but the eviction companies don’t take it seriously and the court does nothing to compel them. The Office of Labor Law and Enforcement says it has never received a complaint. And the Marshals? It’s not their job to get involved in somebody else’s wage dispute.

The American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research is a think tank described as both conservative and non-partisan, and it too has a point of view. Journalist Kevin Corinth captured this expressive quotation from a worker:

We have seen babies crying, grandmas… You do some kind of drugs, so then you don’t care, so you leave them on the curb over there crying, and go on to next one.

Instead of choosing someone professional who says, “I can’t do it,” they choose people who don’t have any feelings anymore, and have given up on life. Because they will get on this truck for $7.

The writer empathizes with landlords, who can’t keep housing on the market if nobody pays them. He also empathizes with the eviction crews, who after all are dealing with some pretty unpleasant feelings. They are homeless people, making other dispossessed and displaced people homeless. In such a role, who could help calling to mind their own parents, partners, or children?

But, Corinth writes:

The true problem is that eviction companies are dehumanizing the homeless men they hire by exploiting their addictions. Rather than being encouraged to serve with professionalism and empathy, they are encouraged to numb their humanity with alcohol.

He even empathizes with the evictees, who are not even given so much as a flyer with shelter addresses or a hotline number. The writer suggests hiring fewer workers for better pay, but, realistically, that idea has a snowball’s chance in hell.

He goes on to say:

Another solution could be to prevent evictions from happening in the first place. Recent research has shown that offering families who are at risk of homelessness modest one-time payment leads to sharp reductions in entries into homeless shelters (and presumably reduces evictions as well).

Whatever the solution, evictions are inevitable. Dehumanizing people in the process is not.

Reactions?

Source: “Eviction Companies Pay the Homeless Illegally Low Wages to Put People on the Street,” WashingtonCityPaper.com, 02/23/17

Source: “Exploiting homeless people is not okay,” Aei.org, 02/28/17

Photo credit: 70023venus2009 via Visualhunt/CC BY-ND

Entering the World of Protected Work

In Iowa City, Iowa, Shelter House helps hundreds of people every year, not only with a place to stay, but with job training and placement. Participants in case management have opportunities to work toward job readiness and employability.

The on-premise computer lab offers workshops in basic computer skills, as well as guidance in applying for housing and food assistance. The job and housing databases are packed with information, and help is available to create a resume.

There are two internal employment services. Fresh Starts is the professional janitorial service, whose workers are employed by area businesses. In the Culinary Starts paid internship program, people learn kitchen and culinary vocabulary, recipe manipulation, menu production, how to use kitchen equipment, and much more.

The website says:

Successful participants will become Servsafe certified and equipped to work in a variety of food service and restaurant settings. The proceeds from our contracted and catered meals go directly towards the food production program and Shelter House’s mission of helping people move beyond homelessness.

In the nation’s capitol, the Transitional Housing Programs for Men who are Homeless are administered by the D.C. Coalition for the Homeless. Six houses of different sizes are home to between 12 and 100 men in various stages of readiness to enter the working world. Some concentrate more on basic supportive services and life skills to prepare for self-sufficiency.

One is the Emery Work Bed Program, described as…

[…] specifically tailored to the needs of homeless men who are employed or in job training… The primary objective is to assist men in sustaining employment and moving into permanent housing. Program participants must be willing to accept case management services, meet with case management staff weekly and develop and follow an Individualized Service Plan.

Eastway Behavioral Healthcare is a private nonprofit mental health agency in Montgomery County, Ohio. In an unprecedented partnership with the county’s homeless service providers and their federal HUD funding, Hope Housing was created.

Eastway’s Laura Ferrell says:

You can’t find a job, you can’t become a productive member of society, you can’t make sure you get all of your medications and keep all of your doctor’s appointments if you don’t know which doorway you might be able to sleep in tonight.

Director Kathy Lind told journalist Thomas Gnau that most of the clients have “a lot of barriers, like mental health or substance abuse, criminal records.” Nevertheless, the time between referral and placement has been as short as 45 minutes. When the residents are ready to go out on their own, the Eastway staff reports, remarkably, “no shortage of landlords who have been willing to work with the program.”

The compassion and conviction are rooted in a hard-headed awareness that helping people get on their feet is a bargain compared to the expenses they could potentially rack up in the form of ER visits, hospitalizations, jail rent, or even such contingencies as winning a lawsuit against the city for one of the injuries that people experiencing homelessness often suffer at the hands of law enforcement.

Hope Housing operates under the “Housing First” model, and, in three years, 48 people have gotten their lives on track and found permanent housing, so it must be doing something right.

Reactions?

Source: “Job Training,” ShelterHouseIowa.org, undated

Source: “Transitional Housing Programs for Men who are Homeless,” DCCFH.org, undated

Source: “Program helps get homeless off streets, into jobs,” MyDaytonDailyNews,com,12/26/16

Photo credit: Alan Light via Visualhunt/CC BY